Have you ever laid eyes on the box art that Advance Wars 2: Black Hole Rising shipped with? It features a towering figure whose countenance is encapsulated by a bizarre crossover between a samurai mask and a police hat – the combination of which is strangely reminiscent of Darth Vader’s breathing apparatus. It’s a little peculiar that this imitator should feature so prominently on the packaging, too, for he is at best the game’s invisible shadow puppeteer, not main-stage villain.

Anyway, Black Hole Rising is the second instalment in the now-dormant Advance Wars series. It retained its prequel’s kindergarten-depth, cookie-cutter story to glue together a few dozen hours of toony, tactical war-themed gameplay – and then took that gameplay and cranked up the difficulty to 11. For novelty a new unit type was thrown in and the roster of Commanding Officers (or COs) enlarged with fresh faces. Otherwise, though, Advance Wars 2 (AW2) played it exceptionally safe. Normally, I’d withhold brownie points for a failure to innovate on an established formula, but given how well both AW1 and AW2 played and the poor design choices evident from NDS Dual Strike onwards, that sameness may be a blessing in disguise.

I’m getting ahead of myself, so let’s backtrack a little. Advance Wars is a top-down, turn-based, tactical warfare game where the player commands the forces of Orange Star in a bid to repel the invading armies of fascists-in-residence Black Hole. That description applies to both the original Advance Wars (2001) and Black Hole Rising, which unabashedly rehashes that exact setup. Somehow, Black Hole has recovered from total defeat at breakneck pace and is once more blitzkrieging the globe. This puts the onus on the player to, first, liberate their own continent from the black scourge and then help embattled allies out of their respective pickles. To make a perhaps inappropriate analogy, this story arch is suggestive of the German Reich’s double rise and fall in the early 20th century. In support of that notion – Black Hole soldiers are even cloaked in intimidating gray Wehrmacht trench coats. But I digress.

In the original Advance Wars, the player spent two campaigns under the watchful eye of hand-holdy CO Nell, learning the ropes. Black Hole Rising assumes you’re streetwise and takes off the training wheels almost instantly, quickly exposing you to the full might of Black Hole’s capabilities. The resulting Campaign mode – the game’s centrepiece – features an island-hopping between allied nations to tackle missions of increasing difficulty.

The core mechanics and rule-set are identical each mission. As hostile commanders face off, they utilise factories, airports, and naval bases under their control to crank out military hardware to destroy the opponent’s units. The limiting factor is cashflow, provided by said facilities as well as cities, which can be ‘captured’ from neutrality or enemy occupation. Units range from foot soldiers to heavy tanks, each with a distinct role on the battlefield. Infantry is cheap and destroyed easily, but invaluable since they’re the only unit type that can capture real estate. Recon units excel at intercepting advancing troops but are no match for armour. Tanks are in-your-face units that ably punch holes through enemy lines, but are vulnerable to indirect artillery and rocket fire. These ranged units, in turn, sport poor movement and no direct combat ability, making them sitting ducks at close range. And on it goes. With some two dozen unit types at the player’s disposal, each with different a construction costs, fortes, and vulnerabilities, the product is an elaborate web of rock-paper-scissors-lizard-spock.

It’s a charming formula that allows for a surprising amount of depth, which is further enhanced by varying terrain fixtures, unique special CO powers that can be brought to bear at critical moments, and the varying placement of starting bases and seizable real estate.

Terrain is simple enough to understand. There are five types in all, from open fields to urban tiles to mountains, each with different defensive and mobility properties. The key is to exploit synergies between terrain and unit type. Park rockets in cities for extra defence and instant repairs should they unexpectedly come under attack. Have tanks rolling along roads for added movement. Entrench mechanised infantry in mountain tiles and they can hold their own against armour, plus peer deep into hostile territory. Keeping units alive is quite essential, even if by the skin of their teeth. Each represents a sunk cost, and when 10 HP reaches 0, they explode in friendly puff of smoke and are cleared from the map. Timely withdrawal allows you to move units to friendly premises, recovering 2HP/turn (out of a maximum 10) to regain full combat strength, or join them up with similarly damaged units – a far superior return on investment.

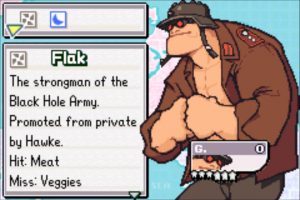

CO powers charge gradually over the course of battle and can be activated to provide certain advantages to your soldiers. Olaf, a gruffly Blue Moon CO, is a winter expert and his Blizzard ability coats the map in icy glazing that dramatically impedes enemy movement for a turn – but leaves his own unaffected. Andy, a youthful over-exuberant Orange Star CO repairs damaged forces in the blink of an eye. CO Sami, outfitted like a female version of Commando’s John Matrix, adds cap-speed bonuses to her already stellar infantry combat ability. There are 19 commanding officers to choose from, and while favourites quickly develop (and specific scenarios narrow the range of feasible COs), Intelligent Systems has done a passable job on the unenviable task of balancing all while keeping each unique.

This brings me to third core component that allows for variation across missions. Occupiable features are scattered across maps in such a way to present enticing targets worth fighting over, both from the perspective of immediate tactical superiority and the wider strategic advantage that comes from owning a superior number of assets. As you might expect, missions habitually start the player off disadvantaged. It does so in two ways.

First, numerically through an income disparity. This is not immediately obvious unless you compare a mission’s starting assets in the game’s outliner, but the AI initial real estate always exceeds the player’s during the opening scramble. Each occupied facility provides 1000 currency per turn. (For reference, an infantry unit costs 1000 to produce, a recon 3000, a tank 8000, and the almighty Neo Tank a whopping 16000). So until capturable neutral assets come into play, you’re on the back foot and must outplay rather than overpower – appropriate for a strategy game, of course.

More subtly, however, many maps feature strategically placed narrow corridors that are pivotal to controlling adjacent swathes of assets. These key objectives are never quite equidistant between yourself and the AI, meaning you’ll either rush them and brave superior firepower, or risk a wider financial deficit and get definitively outgunned down the road. Both the income gap and initial strategic disadvantage are stretchable concepts – that’s the beauty of such design. A game developer can skew the playing field to any extent desirable, which is a clever approach to difficulty scaling that I vastly prefer over alternate solutions – such as enemy-plastering – that tactical warfare games sometimes embrace.

The AI performs respectably on the Normal difficulty. In general, I cannot overstate how easily Intelligent Systems could have faltered here, with game-breaking consequences for a title that leaned almost exclusively on its single-player offering for success in a pre-internet connectivity era. The AI doesn’t act discernibly hare-brained or otherwise transparently throw in the towel to facilitate the player’s victory (I’m looking at you, every Pokémon RPG ever made). That said, I do question the AI’s infatuation with building T-copters, which it eagerly sends behind enemy lines time and again on clear-cut suicide missions. But let’s look at it glass half-full and pass this off as a quirk rather than a covert resource sink.

If you must elicit an AI-related niggle from me, it would be how it displays greater aptitude at stalling for time than punching for all-out victory. Because of this certain COs – such as Yellow Comet’s Sensei – can be high on nuisance factor, especially in the optional War Room mode where he liberally applies his CO powers to repeatedly conjure mechanised infantry onto every occupied city (and these can run over a dozen). Since infantry is easy cannon-fodder, all this usually accomplishes is to inflate the map’s unit count and drag out battles into a protracted, time-consuming grind. Gunslinger CO Grit also deserves mention in this context, since his indirect combat units sport absurd gunnery range that can be frustratingly successful at seizing and holding key terrain.

So, Black Hole Rising shuffles its variables admirably well to create three short-but-sweet, compelling, Black Hole butt-kicking campaigns in Orange Star, Blue Moon, and Yellow Comet (spotting the pattern yet?). However, by the time the Green Earth campaign rolls around, missions start feel a little samey. The game is aware of this, and it’s the point where it attempts to shake things up by fiddling with overarching concepts of unit production and victory conditions. The game handles the new victory conditions competently and soon you are not just capturing HQs, but blowing up Big Berthas and sinking submarine armadas to taste hard-earned victory.

But I feel obliged to call out the misstep that is removing unit production since it entirely interrupted the game’s flow for me. I’m talking about the mission entitled “Sea Fortress”, which features an airborne attack by Green Earth CO Eagle on 8 minicannons shielding a maritime causeway. At your disposal is a fixed number B-copters, bombers, and fighters squaring off against both hostile avian forces and the minicannons themselves, which produce lethal cone-shaped blasts that seriously damage anything caught in them. My gripe is this. By removing the capacity to manufacture new units, Advance Wars’ usual strategic dynamism is supplanted with pre-set stock variables on each side. This reduces the ways in which a battle can play out, thereby forcing a search to discover optimal unit movement patterns through frankly uninteresting trial-and-error. With razor thin margins for error even on the standard difficulty, you’re likely to fail a few times – with frustrating mission restarts the result. This is explicitly not fun. I worried that this regressive mechanic would appear repeatedly during the game’s finale, but thankfully Intelligent Systems grasped its inherent clash with the game’s core philosophy and confined the variation to one-off.

The persistent player is rewarded with a shot at the campaign’s Hard mode, which features the same missions calibrated to punishing difficulty. A more modest challenge is found in the episodic War Room, where you can freely select unlocked COs to complete self-contained challenge maps for highscores and in-game currency – spent to unlock yet more battle maps, COs and spanking new army livery. It’s an addictive distraction that, besides enjoyable on its own merits, allows for the honing of skills when inevitable setbacks occur in Campaign mode.

An honorable mention goes to Black Hole Rising‘s soundtrack that does a stellar job of reinforcing the identity of the CO you’re playing as. Hillbilly Grit gets a plucking, laid-back acoustic guitar track; Samurai Kanbei an oriental piece so excessively jangly it could alsmost be construed as insulting; and the pantheon of Black Hole COs make do with blood-and-iron march music that comes down midway between Shostakovich’s Leningrad Symphony and the national anthem of the Soviet Union.

In fact, it would be more accurate to state that CO theme music, to a large extent, is personality-setting rather than affirming. Black Hole Rising does not bother to flesh out commander backstories, and therefore absolutely zero character development takes place across the game’s paper-thin story arch. Bar the theme music, then, COs are cardboard cutouts; mere collections of sprites that form colourful tenterhooks to hang up particular sets of battlefield abilities. This disregard for narrative impact extends into Black Hole Rising‘s toony combat, in which it places absolutely no emotion, and COs do not seem least bothered to send unit after unit to a gunpowdery grave. (Apart, perhaps, from the very real chance that it deducts from obtaining a mission’s highest decorum, an S-rank rating.) Not that this distinct lack of narrative presentation – or identity, even – bothers me all that much; Black Hole Rising is still a fantastic game in its absence, though I can’t help but wonder if the Advance Wars series’ splash would have been more profound and enduring had it excelled more than just mechanistically. (The success of Fire Emblem comes to mind, which – especially in recent years – pairs strategic excellence with rich storytelling.)

Advance Wars 2: Black Hole Rising is available on the Wii U’s Virtual Console – here’s to hoping it will also hit the Switch – and I highly recommend you take it for a spin. It’s best enjoyed in short bursts so the gameplay won’t saturate you for the lack of a story, and thanks to the now integrated internet connectivity, the VC version poses the very real possibility of duking it out against human opponent. Just… Have mercy on your challenger. Don’t play as Grit.

P.S. The poor man’s Darth Vader, by the way, is this chap here – Sturm, dictator of Black Hole.

- Harvest Moon 3 (2001) - March 5, 2020

- Pokémon Trading Card Game 2 (2001) - February 5, 2020

- Yu-Gi-Oh! Dark Duel Stories (2002) - January 5, 2020