Pokemon Prism is dead; long live Pokemon Prism!

To discover Pokemon Prism’s humble beginnings, we must travel backwards in time to 2008 – over a decade ago – when KoolBoyMan (KBM) hatched the ambitious plan to create a nostalgia-fuelled Pokemon RPG in the visual style of GameBoy classic Pokémon Crystal. For years KBM chipped away at the herculean task of designing an entirely new adventure by himself, sharing snippets of progress with an expanding complement of eager onlookers as Prism grew in scope and completeness. The lone developer’s persistence paid dividends when in late 2016, a YouTube trailer of the near-complete game went viral, whipping up mass enthusiasm at this evidently mature and well-polished retro fan-title. Inevitably, however, this public interest also attracted IP holder Nintendo’s attention; soon after, an instruction to cease-and-desist from Prism’s further development landed on KBM’s doormat, threatening to unceremoniously scupper the project mere days prior to planned beta release.

Fortunate it is, then, that the dispersion of bits and bytes is hard to quell completely by court order. In a feat of eleventh-hour salvation not altogether uncommon to fan projects, a benevolent soul leaked Prism’s source code to the wider web, where it was downloaded freely by thousands. More so, the raw file release prompted the formation of an anonymous collective who stylised themselves the “Rainbow Devs”. Valiantly vowing to carry KBM’s vision to completion, Prism’s fate has been in their hands ever since – and boy, is it good.

It’s a beautiful summer’s day, and your outdoorsy family spends it hiking in the mountains near your hometown. As night falls, a pint-sized bonfire lights the makeshift campsite, and to fan its crackling flames, your mother requests that you collect some firewood. No sooner have you ventured downhill gathering twigs and branches, however, than a sudden rockslide barricades the passageway whence you came. Hopelessly trapped, the unexplored depths of a nearby cave system are your only escape from this predicament.

In these elaborate tunnels you unexpectedly encounter a timid Larvitar who appears to be wandering aimlessly. Relieved to have found a partner, you happily team up, and with joint effort you navigate the subterranean tunnel network. As you resurface – or rather, plummet towards the cave’s mouth through a gaping aperture – you reassuringly find yourself in snow-capped Caper City, where Larvitar is reunited with its long-time master, a lab-coated professor by the name of “Ilk”. Oddly, however, Ilk seems wholly unconcerned with his Larvitar’s well-being (nor, when you relate your tribulations, is he compelled to mount a rescue expedition for your dear mother who, we can only assume, is still trapped in the mointains.) Rather, Ilk promptly dispatches you to a nearby town to chase off a generic thug who has been pestering his brother. And the Larvitar you generously get to keep.

With that rather bizarre sequence of events, Pokemon Prism kicks off.

When word of Prism first reached me, I was led to believe that, like so many ROM-hacks before it, Prism was a mere reimagining of the original GBC games, a tweaked and optimised experience. (Not that I have a problem with this; Polished Crystal, precisely such a remake, is pretty good.) But Prism is so much more than a remake. Yes, the game includes portions of Kanto and Johto – the overworlds from Generations I and II – but prefaces visits to these regions with a lengthy, entirely original adventure spanning the custom, built-from-scratch 8-bit regions of Naljo and Rijon (first seen in Pokemon Brown). Naljo in particular is designed superbly and virtually indistinguishable from first-party gameworlds.

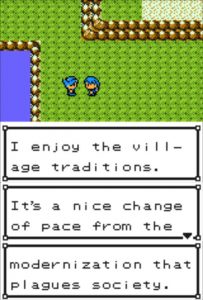

Besides being a brand-new adventure, Prism caught my eye on a thematic level. It is borderline platitudinal to observe that the Pokemon-universe exists inside a bubble of bliss deliberately devoid of sociopolitical commentary and Shakespearean themes (for example, Pokémon titles have, until very recently, assiduously avoided the topic of death.) Prism on the other hand, not bound by Nintendo’s modus operandi, is unafraid to insert more weighty thematic material into a Pokemon experience, not least by taking the occasional ponderous view of life’s subtler and grimmer themes. Most immediately visible, however, is the game’s concern with the environment.

You see, Prism explicitly sets up Naljo as the unhappy frontier in the see-sawing tension between technological advancement and urbanisation on one side and environmental preservation and traditional values on the other. The game ably explores this subject matter through a series of well-crafted sequences in its first moiety, adding a meaningful message to the usual morally stale path to the Elite Four. I found this to be a breath of fresh air, and it is an interesting revelation that the Pokemon series can sustain a modicum of real-world realism and not lose its fairytale magic, provided it is balanced out by some light-heartedness – which Prism displays in abundance.

Yet these convivial sequences, too, are a different animal compared to first-party titles. Pokemon Prism dustbins the official games’ political ultra-correctness by writing in some stylishly edgy dialogues. Take its punchy one-liners that would never pass Nintendo’s parental guidelines. Prism’s post-battle dialogue routinely had me snorting with laughter: the second trainer I met commanded me in no uncertain terms to “wipe that smirk off my face” after Larvitar had trashed his Sentret (the admonition, of course, had the exact opposite effect). And as I departed Naljo for the first time to enter the neighbouring region of Rijon, I was surprised to encounter some serious xenophobia as an elderly gentleman demanded forcefully that I’d “better not be from Naljo.”

Prism’s audacious playfulness also radiates from its cast of wacky characters. Take Fairy-type Gym Leader Brooklyn for an example. Brooklyn is a hopelessly entitled, clingy fashionista who so stifles her pet Totodile that it all-too happily defects from her custodianship and, amidst much hilarity, joins your party to escape her clutches for good. And then there’s the ramshackle organisation Team Palette, who play the part of Prism’s villains-in-residence and invariably go about in multicoloured spandex outfits very clearly modelled after the Power Rangers.

Abandoning convention both thematically and narratively is a risque move for the serious fangame. Many projects have stumbled trying to seat the Pokemon franchise in a more realistic framework, only to have this rough fit grate away the series’ magic like sandpaper. Pokemon titles are hugely popular partially because they are an unblemished form of idyllic escapism, and adding saddlebags of reality often burst that bubble. Yet unlike its assembly of fire-breathing trainers Prism never quite burns itself in this task, knowing always just how much gravitas a scene can sustain, and where to draw the popular line. Its environmental exposition is executed with relative poise, and uncharacteristic dialogue never descends into juvenile rudeness in a bid to attract attention – again, this in contrast to the plethora of less refined Pokemon ROM-hacks that opt for a confrontational tone in lieu of inspired writing and come off primitive as a result. Rather, Prism inserts just enough atypical exchanges into the Poke-universe to pleasantly subvert my expectations, often to great hilarity, which generally punctuated the classic gameplay nicely.

That is – during the first half of the game. Until the halfway mark, comic relief Team Palette appear to be the usual half-baked crime syndicate ultimately dismantled by a 12-year old that we’ve come to love from the Pokemon series (though their battle prowess is nothing to sniff at). However, where Team Palette differs from Team Rocket – besides an Eevee-obsession replacing a Koffing-infatuation – is that Palette’s habitual scheming actually turns out nefarious. That’s fine, and perfectly in keeping with Prism‘s grayshades universe. I generally approve of a somber note in games (the decidedly political Tactics Ogre series is my all-time favourite), and I was excited to experience the dark underbelly of the Poke-verse Prism seemed destined to reveal. However, rather than continuing to trundle down realism road, Prism instead took a sudden sharp turn for the mythological, and in doing so, for the first time, didn’t get it quite right.

By committing to this mythological turn, Pokemon Prism forfeits the balancing act between the credible exploration of real-world tensions and tongue-in-cheek humour that had hitherto been so effective. Worse, the wishy-washy legends wheeled in to take its place are not at all convincingly presented. If you don’t mind the minor spoiler: Team Palette is intent on reviving the legendary “Guardians” of Naljo: a quartet of all-new omnipotent Pokes that once held sway over the region but who were ultimately sealed away to insulate mankind from their unfettered power. Once the tales of the abject misery that they brought upon humanity are communicated to the player, Prism dons an exclusively grim mask that doesn’t come off until the Elite Four are defeated.

By committing to this mythological turn, Pokemon Prism forfeits the balancing act between the credible exploration of real-world tensions and tongue-in-cheek humour that had hitherto been so effective. Worse, the wishy-washy legends wheeled in to take its place are not at all convincingly presented. If you don’t mind the minor spoiler: Team Palette is intent on reviving the legendary “Guardians” of Naljo: a quartet of all-new omnipotent Pokes that once held sway over the region but who were ultimately sealed away to insulate mankind from their unfettered power. Once the tales of the abject misery that they brought upon humanity are communicated to the player, Prism dons an exclusively grim mask that doesn’t come off until the Elite Four are defeated.

As it stands, I think this is a mistake – once Team Palette turns to the dark side, all frivolity disappears from the game and, for the first time, the good-ol’ Pokemon magic fades. Some of the awkwardness of this tonal U-turn is undoubtedly because the Guardians arch was narratively unpolished when Nintendo’s cease-and-desist hit, and KBM publicly stated that he had planned to devote two full months to polishing it up. Even so, in its present form, the arch’s delivery relies heavily on deus ex machina-like twists that prevented me, at least, from becoming fully invested in this part of Prism’s story. Should the Guardians-tale be fleshed out better in future patches by the Rainbow Devs, the transition from contemporary to mythological may be less rough and the Pokemon magic – possibly – won’t be punctured.

—

Right, let’s talk about Pokemon Prism’s gameplay a little, because mechanically, the game makes some interesting small (and original) changes to the Crystal base ROM. These tweaks subtly alter standard Pokemon RPG adventuring to inject novelty and create new gameplay options. Most visibly, Prism adds forms of Pokemon map interaction that transcend the staple uses of Fly, Cut, Dig etc plus the classic “moving up to an obstacle and pressing A”. In a few stretches you actually get to play as one of your Pokemon, hopping around ungainly to solve little puzzles. These puzzles themselves, too, have been touched up. Cave systems now sport the occasional y-axis, with an underground side-view that invokes the coin collection rooms of Super Mario Bros. Single-tile chasms in this side-view – as well as the overworld – have been made jumpable with the right equipment, adding hiding places for TMs, items, and unique Pokemon.1There are also minecarts that permit travel directly between cave systems. Besides being a rapid way to get around, Prism uses this ingenious innovation to create hidden areas with items, TMs, and unique Pokemon. And finally, gym leaders are no longer necessarily confined to a 5×2 building in next town over. I found one camping out in the heart of a forest in total harmony with nature; another was holed up in a cave, proudly proclaiming his preparedness for the inevitable end of the world to all who would listen.

To add to the innovations, Prism backports essential quality of life improvements made in Gens III to VII. TMs are reusable. Pokemon no longer faint from poison outside of battle but are instead whittled down to 1HP and then cured. A text pop-up facilitates Repel-chaining without revisiting the menu each time. When capturing a wild Pokemon, you gain normal EXP as though you won the encounter. And perhaps most importantly, EXP is no longer divided up between combatants as it was in the original Crystal. Instead, each participant gets full EXP, just like in Pokemon Sun & Moon. This makes it possible to cycle through a full team of 6 in, say, a trainer battle and reap the maximum EXP reward from a particularly juicy target, such as an early-game Butterfree or a wild Yanma. In the context of base Crystal (or indeed Sun & Moon) this would absolutely babyfy the game and, nurtured as I am by my classic Pokemon experience, I would consider this extremely exploit-y. In Prism, however, I’m actually okay with it, as it is arguably a necessary compensatory mechanism appropriate for the level of challenge Prism poses. (More on this below).

And then there’s Pokemon themselves. Tall grass is packed with a more interesting variety of species than we’re used to seeing – I spent my opening 20 minutes of game time lumbering about the first 7×5 strip of greenery in amazement at the diversity of what showed up. I positively adored not having to fight off eight dozen Rattata / Zigzagoon / Bidoof before something half-decent emerged – because viable Pokemon are ubiquitous. By the time the first Gym rolls around, even the most silver-tongued player would be hard-pressed to justify not having all-around type coverage. And trust me, you’ll need it, because Prism can be punishingly difficult – even when factoring in the quality of life improvements re-introduced from recent Generations.

And yet… And yet I wish Pokemon Prism had taken its innovations just one step further. As it stands, the game doesn’t fully exploit the space of opportunities that its own novelties provide. Let me explain. Prism is hard. Hard-as-nails, at times. To this effect it encourages broad type coverage early on. It practically begs you to maintain a well-rounded team.

I would love for the Prism reimagination to do away with the hard limit of six party Pokemon.2Looking back at this review three years on, it’s interesting how Pokémon Sword & Shield have done exactly this by making your Pokémon PC accessible from anywhere on the overworld, permitting free party swaps at all times. I’ve never understood why this cap exists in the first place – surely a trainer can stuff more than six pokeballs into their backpack. In fairness, the often schoolboy difficulty of Generations I to VII made the effort to devise a balanced team of six Pokemon entirely superfluous – the player could simply steamroll the games with, say, a Charizard, reducing proper team-planning and building to optional.

However, Prism is certainly not a walk in the park and ramps up the challenge quite dramatically compared to first-party titles. Unless you’re averse to Repels and willing to spend considerable time grinding – I am neither – you will inevitably find yourself playing catch-up to benchmark Gym leaders, and even to run-of-the-mill roadside trainers. (To illustrate: I had a glaring weakness to Water in my initial team, and a plain-old Fisherman’s level 27 Milotic kindly pointed that out to me by wiping my entire party.) Add to that the wide variety of available Pokemon typings from the get-go, plus some entirely new ones, and it’s clear what KoolBoyMan prods you to do: build wide, not tall. Yet at all times, amidst the bevy of choice, we can only carry six, which now feels like a draconian restriction. To be clear, I am not advocating to extend the scope of battles to a 10-on-10 free-for-all or such, but for crying out loud, let us carry eight to ten and select our preferred sextet prior to each trainer encounter.

I only see upsides. Greater numbers will offset the punishing backtracking in Pokemon Prism: caverns are common, lengthy and hard while funds to blow on Potions are scarce, and restorative retreats to the PokeCenter are therefore frequent. A larger party would also ease the steep level creep, which becomes particularly noticeable from the 4th Gym onwards.

I’ll give you an example of an area where level creep and excessive backtracking – perhaps the most noticeable such occurrence in the game – combine to create an occasionally frustrating experience. The image over to the side depicts the long, winding, trainer-packed pathway carving through the Haunted Forest. A standard playthrough has you traversing it multiple times to solve a roadblock puzzle using colour-coded gravestones in the adjacent cemeteries. Puzzle solved, you’ll enter an isolated condo containing your objective – a building that is inhabited by yet more trainers. None of these trainers are wimps, either – their Pokemon levels match yours, and they sport movesets largely effective in AI hands.

Since you’re likely to be under-leveled at this point, it’s imperative to spread EXP widely evenly. The natural solution is to rotate Pokemon in and out of battle, but as each tanks an inevitable hit on each switch-in they’ll be out of contention for the next fight. Between a damaged party and a lack of potions, you’ll be making a lot of round trips through those darned woods, even – spoilers! – riding the bullet train back to Naljo each and every time to heal, because the town bordering the Haunted Forest is devoid of a PokeCenter. This setup is not a recipe for a good time, but if you plan to defeat upcoming Gym Leader Edison – hardly a pushover – it’s entirely indispensable that you maximise the EXP yield from trainer battles. (Grinding wilds for parity is possible, but infinitely tedious.) My point: a larger party would feel like fair compensation. I don’t know that the parameters of Prism’s programming allow for such redesign, but I would absolutely love it. (Note: Rainbow Devs ultimately implemented an early EXP Share to flatten the curve.)

Moreover, with the most interesting, viable cut of the Pokemon pantheon at our disposal I easily can – and want to! – fill a party of six twice over with personal favourites. I don’t want my B-team to gather digidust in the bank – nor have them join the ranks of the orphanage (which is another awesome innovation, by the way). No, I want to dynamically maintain as wide a battle-ready group as possible. Indeed, the team-building possibilities are elevated to unprecedented heights in Prism compared to the Gen II base-ROM, and it would be fantastic if Prism allowed us to carry that logic through to its natural conclusion and maintain an eight to ten- man team of battle-ready ‘Mons. Not to mention that, like in the original GBC games, one to two party slots are routinely taken up by HM slaves.

Yet in the interest of full disclosure, a part of me takes the opposite view. In fact, one can conceive the frustration that comes with having an EXP-starved, undersized party as an essential, constitutive part of the Prism experience – a throwback to an era when games were dastardly difficult, not cakewalks. Seen in this light, Prism knows its audience better than the audience knows itself and is exploiting that understanding to draw it in. KBM has stated that Prism targets Generation Y for whom Crystal was the defining Pokemon experience all the way back in 1999 and who are seeking a Crystal-esque nostalgia trip coated with a layer of maturity. In a way, Prism resonates perfectly with this target demographic as it delivers a challenging game that respects the mature player’s intelligence who, in turn, through sheer delight with this Pokemon adventure custom-built for them, reciprocate in kind by respecting the hurdles the game throws at you – and then surmounting them. It’s a subtle thing – but if Prism had been the standard Pokemon pushover I would not nearly have enjoyed it so much, nor become so invested in it. 3Though I think that with a little bit of tweaking, a larger party and high difficulty could co-exist.

Because invested I became. I spent an inordinate amount of time for a grown man planning the team I would use to take on the Elite Four. In my mania I even resorted to Crystal-era DV calculators to figure out which of 7 Ralts I had painstakingly collected boasted the highest ATK stat and thus packed the greatest punch as a future Gallade. I downloaded a Prism type chart to help plug holes in my offensive type coverage and interlock defensive typing to cover up glaring vulnerabilities. In other words, I did all of the stuff I didn’t do as a kid, when my cousin’s lv100 Pidgeot tanked all of Yellow and my lv90-plus Gengar ate all of Gold.

I do note some balancing issues in the metagame. Many moves have been backported from future generations, but not all. This results in some strange selectivity that benefits particular Pokemon while enfeebling others. There is, for example, strange selectivity in entry hazards. Lava Pool, which burns Pokemon on switch-out, is a fabulous (if slightly overpowered) new addition, but Stealth Rock and Toxic Spikes are missing. Similarly, priority moves Aqua Jet and Bullet Punch have been transplanted, but Ice Shard hasn’t, curtailing the potential of Mamoswine and Weavile. Physical Ice moves are lacking in general: only Ice Punch exists; this compared to Blizzard, Ice beam and new addition Freeze Burn (140bp) on the special side. And there is no U-Turn (crying Scizor) or Focus Blast (crying Gengar). I don’t know if these meta-imperfections are the consequence of Prism’s untimely leak, conscious design decisions, or programming restrictions imposed by the underlying Crystal ROM, but it feels a little arbitrary.

Pokemon Prism also stumbles over its own ambitions when it comes to the new typings that are introduced. Gas, Sound, Prism, and Tri are a noble attempt at shaking up a type chart that has been essentially stale since Gen II (the addition of Fairy in Gen VI excepted), yet the new type comparison is not intuitive and I find their balance a bit wanting. Sound is weak to an awful lot without sporting equal benefits to compensate. The same could be said of the Gas type, which adds offensive versatility to, say, Weezing and Gengar with the powerful Lewisite (Gas, 90 SpAtk), but also saddles them with a plethora of weaknesses (Gengar’s Ghost/Gas, in particular, is a really poor typing – though did not prevent me from running him). Finally, the inclusion of Tri seems entirely unnecessary, since like the eponymous Prism-type, it is normally (1x) effective against every other type and only one move, Tri Attack, falls into this category.

Pokemon Prism also stumbles over its own ambitions when it comes to the new typings that are introduced. Gas, Sound, Prism, and Tri are a noble attempt at shaking up a type chart that has been essentially stale since Gen II (the addition of Fairy in Gen VI excepted), yet the new type comparison is not intuitive and I find their balance a bit wanting. Sound is weak to an awful lot without sporting equal benefits to compensate. The same could be said of the Gas type, which adds offensive versatility to, say, Weezing and Gengar with the powerful Lewisite (Gas, 90 SpAtk), but also saddles them with a plethora of weaknesses (Gengar’s Ghost/Gas, in particular, is a really poor typing – though did not prevent me from running him). Finally, the inclusion of Tri seems entirely unnecessary, since like the eponymous Prism-type, it is normally (1x) effective against every other type and only one move, Tri Attack, falls into this category.

Of course, Pokemon Prism being in active development, the meta is constantly updated as TMs are scrapped in favour of others and movepools balanced. If the Rainbow Devs keep true to their word, there will be ample time to refine and polish before Trade and Battle functionalities are implemented – which is a stated medium term goal.

At the time of writing, Prism v0.93 b197 has just been released, which is a cumulative update that fixes oversights and bugs inherited from the premature patch leak and makes the game intensely – and safely – playable, insofar as it wasn’t already. Provided the faceless collective holds together we are promised a series of future content updates focussing mostly on the post-game. As it is, some content is missing in high-level regions, particularly in Johto – which is of course Crystal’s original continent that is now visited in the late-game. On the whole, Prism’s most glaring omission concerns the finale to the questline of the mythical Guardians. KBM had originally allocated a cool two months of development time for this purpose, and it remains to be seen whether the Rainbow Devs will truly assume a creative mantle of this size and bring the story to a (more) satisfying conclusion.

But honestly, even if they contented themselves with polishing up the 98% of planned content that is already there, that would be more than fine. In its present state, Pokemon Prism is already a highly successful, expansive and well-rounded game. With 20 gyms across five regions (even if some are only partially accessible) and tons of original content, it is arguably closer to definitive Pokemon experience than any ROM-hack – dare I say official release, even – has ever come.

—

Note: The playthrough of Pokemon Prism was started on version 0.93 (b160) and completed on version 0.94 (b200).

Update: As of May 2018 (version 0.94, b227), Prism still awaits finalisation of the post-game arc and trade functionality. The Battle Tower is now fully functional.

Update: As of July 2020 (version 0.94, b237), type chart additions have seen a series of refinements.

- Harvest Moon 3 (2001) - March 5, 2020

- Pokémon Trading Card Game 2 (2001) - February 5, 2020

- Yu-Gi-Oh! Dark Duel Stories (2002) - January 5, 2020