Many classic RPGs play their storyline cards close to their chest, going to great lengths to craft and sustain a visceral sense of mystery and wonder while you attempt to discover your identity, separate friend from foe, and seek out your destiny. This allows for a journey filled with revelations and plot twists, and leaves you always wanting to learn more.

Fire Emblem: the Sacred Stones takes a different approach. Upon hitting the START-button, Sacred Stones spits out an intricate world history that reads like a two-sheet synopsis of a 600-page Game of Thrones novel. Leading with a narrative infodump seemed like an odd way of trying to hook a player. Sadly, odd design abounds in Sacred Stones, as I was about to find out.

What I gathered from Atlas Shrugged Sacred Stones is this. On an island – why is it always an island? – are found a bunch of small-ish independent states, each reigned by a brawny-looking, neatly-groomed fellow for a king. For reasons unknown one of these rulers has recently gone stark raving mad and launched a surprise attack upon his unwitting neighbours. Thus on the back foot, it is your job to reclaim lost lands and depose the mad emperor, who just so happens to derive his strength from the darkest of dark pacts with an unnamed netherwordly figure. Of course, it wouldn’t be a Japanese production-line RPG if the supernatural were shunned, and by mission 5, the map is inundated with giant floaty eyeballs.1On a side note, unlike the ‘Tactician’ persona in recent Fire Emblems, the player has no explicit physical presence in Sacred Stones – testimony to how Fire Emblem has evolved over many iterations.

The story’s setting, then, is a little rote, but neither a stock premise nor an unimpressive opening predispose the telling of a tale to failure. The world of penmanship is filled with examples of slow-off-the-block writing that, once it grabs you, never lets go (Firefly!). Yet Sacred Stones at best muddles through, following up its false start with difficulty in establishing a compelling cast fuelled by credible motivations, resulting in an overarching story that feels both disjointed and immaterial. This is rather unfortunate, because without superb writing to sustain Sacred Stones, it devolves into simply a loose collection of tactical combat maps that aren’t very good either.

But let’s talk about the story first. I was left scratching my head about the main characters’ surprisingly flippant attitude towards island’s grim state of affairs as made abundantly clear in Sacred Stones’ textbook-length opening. Faced with a world overrun by fiends from the shadow realm, a mad king who’s subjugated half the island, and the fate of the continent’s royalty in the balance, the protagonists respond with a whimsical, impulsive optimism that reads as complete and total naïveté. Could it be, you say, that the cast initially doesn’t have full information, and are simply underestimating the magnitude of the threat? Perhaps, but there is never a tonal shift. The same uncompromising youthful over-exuberance persists throughout the adventure.

Instead, I think, this is reflective of a favoured Japanese theme – the purity of youth, unwaveringly righteous, sanguine and bearer of the divine will, prevailing over the corruption of ancient evil. That’s cool, it’s a JRPG after all. But to a European audience unacquainted with this tradition, the distance separating light and dark / good and evil in Sacred Stones is so vast and absolute that it becomes challenging to perceive rationality in either. And I’m not just talking the broad strokes of Sacred Stones’ over-engineered plotline – no, this dichotomy also trickles down into support conversations where a good 50% of the cast emerges as infallible epitomes of innocence. Collectively endowed with the personality of Skies of Arcadia‘s Fina, they are caricatures of real people and a far-cry from complex, mortal individuals.

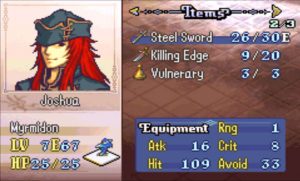

It doesn’t help that new allies are introduced at breakneck speed. Each has their own combat class with strengths, weaknesses, and sometimes special abilities, and their rapid addition to the roster presents you with welcome strategic choice a handful of missions in. However, the narrative cost that comes with this motley assembly of random individuals is a sense of inchoateness. Few have particularly profound motivations for joining protagonist orphaned lordling Eirika in her crusade, let alone for sticking by her when things get hairy – that is, beyond the solidarity of simple camaraderie.

Essentially, I get the impression that each character in Sacred Stones was initially conceived as a vehicle to accommodate a particular collection of combat properties rather than for any given narrative purpose. (The logic being “we – the dev-team in charge of combat – need an X number of swordsmen, X brawlers, X archers, X wizards, and X healers to craft balanced combat, so make sure you – the narrative team – have written ’em all into the story by mission six.”) It’s an interesting thought. The classic RPG development workflow in the biz is to first create a story filled with characters of instrinsic value, and only then, once the narrative-side is locked down, to begin the process of assigning particular battlefield talents to available character moulds.2Crudely simplified, of course. In practice this process is a two-way street, though narrative design will nearly always be the bedrock (or at least start sooner) as game(play) design follows and adapts to the material it is presented. But Sacred Stones very, very much plays as though a character’s battlefield purpose was the driving force in the creation of this particular cast, not narrative necessity.3Double Fine’s Broken Age development documentary is a great resource for learning about the complementarity, and sometimes tension, between narrative and gameplay design. Subset Games’ talk about designing Faster Than Light is a great example of a design process turned on its head.

I say this, firstly, because individuals drift loosely into the story in the cast-forming opening half of the game, even by Fire Emblem’s notorious standards. Team-up speeches are rushed, unimaginative affairs; as a representative example, the line “Let us join you for a while – we have nowhere else to go” certainly captures this spirit. And abundant “remember when”-anecdotes intended to give backstory to character portraits are a thin veil for the most ad hoc form of storytelling. The cumulative result of repeated mystifying allegiance-swearing is that the wider narrative, too, feels like a jumbled-together, incoherent, post-rationalised tale.4 Dialogues in Sacred Stones are not at all aided by a translation that reads like it was completed over a long weekend. It may well have been – historically half of all Fire Emblem games never made it outside of Japan and NA/EU releases used to be numerically modest, perhaps afterthoughts.

In fairness, some of this clumsiness vanishes after the roster stabilises. Even so, the makeshift crew never quite gels to the extent appropriate for a Fire Emblem title and typical interactions designed to flesh out individual character and build true esprit de corps feel uninspired and never quite hit their stride as they do in, say, Awakening.

This is regrettable; after all, it is quintessentially Fire Emblem to pad adventures with backstory-rich “support conversations” that make the corners of one’s mouth twitch and contain just the right amount of goofiness, suspense or even innuendo to want to play the next chapter. Two decades into the series, these nested narratives are a mastered art and an undisputed driving factor in the runaway success of recent instalments Awakening, Fates and Heroes. It certainly doesn’t help Sacred Stones that the encamped-caravan setting where such interactions usually take place is an innovation that post-dates this game, and its absence casts a long shadow.

In any case, if battle map design took precedence over narrative design, then we’d expect the strategic experience to be outstanding, right? All seems good at first. Sacred Stones is built around Fire Emblem’s rock-solid and unchanging combat fundamentals: the sword-axe-lance weapon trinity at the core, the terrain interactions, the usual 20-some feudal characters designed to support multiple direct combat classes with various strengths and weaknesses, supplemented by a dollop of wizardry and bow-sniping – it’s all there. Maps are peppered with strategically placed chests to unlock for loot, villages to liberate for helpful gifts awarded in gratitude, and enemy soldiers to be mugged for bounty. Sacred Stones is built from quintessential Fire Emblem DNA, and that the game is still an entertaining romp fifteen years post-release is testimony to the timelessness of Intelligent System’s formula.

However, look a little closer, and we find a quaint experimentality unknown to modern entries in the franchise. Some of Sacred Stones’ experiments, however, are a touch player-unfriendly, easily exploited or hamstrung by poor AI, making them feel like ill-considered attempts at combat embellishment clumsily bolted onto – not integrated into – Fire Emblem’s established mechanics.

Take, for example, the ‘Arena’ structures present on certain tactical maps. In the midst of battle, the player can choose to direct a unit onto an Arena to conduct a prize fight against a randomly generated unit. Winning this battle yields lavish earnings that multiply with each successive foe defeated. It’s an attractive proposition; however, the game neglects to mention that failing to back out of a losing fight results in the irreversible death of the unit involved, and not a simple Gold loss as I had naively assumed. This made for an extremely nasty and entirely unsignposted surprise. (Rest in peace, Vanessa.).

Arenas are newbie traps. Life-or-death risk-taking for inconsequential monetary reward (funds are never a problem throughout Sacred Stones) is not ever worth it. There’s no place for reckless gladiatorial fights-to-the-death on campaign maps that are themselves life-or-death engagements. I would have loved Arenas as a non-lethal, optional game mode accessible via a menu screen, similar to the challenge maps from Knight of Lodis or Advance Wars’ Battle Room. Exclusive equipment could have been available through it, new characters made recruitable, and additional maps unlocked. But alas, this wasn’t meant to be.

My dislike for story-mission Arenas isn’t to say you can’t use them to your advantage, however. Enter Seth, your pre-promoted Paladin wrecking ball who is perfectly suited to milking the Arenas for all they’re worth – disjointedness be damned. Prefab OP tank Seth stoically tempts waves of enemies to commit ritual suicide on his spear as nobody, including random Arena fighters, can lay a finger on him. Have Doombringer Seth soak up EXP like a sponge, and he can easily solo the game. Even if you were to consciously under-utilise Seth in favour of raising up squishy EXP-sinks like the aforementioned Pegasus Knight Vanessa or Aspiring-Pirate Ross, he will still beat the snot out of anyone by game’s end. Fire Emblem veterans oft consider unmodded Sacred Stones a straight-up cakewalk, and much of this criticism traces back to Seth.

But I think there’s more to it. Pre-promoted Knight-like characters are a staple of Fire Emblem (Path of Radiance had Oscar, Awakening had Frederick, and so on), and none of these games were walks-in-the-park like Sacred Stones. So what gives?

Well… AI. That’s what gives. Seth couldn’t be a one-man meat grinder if the AI weren’t so easily manipulable. Even on Hard, Sacred Stones isn’t very challenging compared to, say, Awakening.

The problem stems from the way enemy troops act on their unit-specific movement ranges. As a general rule, each unit will remain rooted to one spot until you, the player, actively stray into their “aggro zone”, which consists of their movement range plus an extra tile (or two) they can attack into. Like in Advance Wars, pressing the R-button will provide you this information. However, quite unlike in Advance Wars, the majority of AI forces will never strategically reposition to afford themselves better fighting chances on the next turn. Instead, they stand transfixed, watching their comrades get picked off one by one until they’re next. You can readily abuse this programming by moving one tanky unit – Seth – into a full group’s range, who will respond by collectively descending upon him like a pack of hungry hyenas even though they can barely chip his armour… And subsequently die to a few swift counterattacks of his spear.

Combat, then, is often predictable and undynamic. Each set of enemies is effectively a “pod”, like in XCOM 2, comprising a small puzzle that can be tackled in isolation without worrying about the larger enemy force on the map. But unlike in XCOM, you’re not on a turn timer, and you invariably have an overwhelming numerical advantage in each mini-encounter. This, plus sledgehammer Seth, makes the game child’s play, despite the ever-present worry of permadeath.

In a bid to keep things interesting, the game throws frequent curveballs at you. Sudden reinforcements popping up to your rear are Sacred Stones’ go-to solution. Even if these seldom tilt the overall scales of battle, they may still catch out a lone or laggard unit – which can be rather frustrating until you develop a sixth sense for unannounced visitors or simply learn the battlefield triggers to hardcoded sudden arrivals through trial and error.

One of Sacred Stones’ better ideas is to sprinkle points of interest around the mission map that are, as opposed the overall objective, time-sensitive. This might be a village about to be ransacked by a bandit mob that promises a tantalising reward if afforded protection, or a besieged neutral (green) character you can recruit should they survive an enemy onslaught. Such incentives work reasonably well at drawing out riskier play if, like me, you’re determined to see the a game’s full cast and fill up your equipment racks. Should you not care for either, these side-missions are easily ignored in favour of a no-risk playstyle.

Sacred Stones’ final trick is to lower a fog-of-war curtain over the battlefield on certain missions. This fog obscures enemy units, which is a technique that was used to great effect in other games. Remember how in Advance Wars you could hear enemy units moving beneath the fog? Synchronised footfalls for infantry, the mechanical whirring of caterpillar track for tanks… There isn’t any of that here. In Sacred Stones, fog is designed to create the illusion of dynamism, i.e. the suggestion that stuff happening beneath the veil, which there in fact isn’t, because all troops are rooted to the spot. You can stay out of trouble by simply edging your units forward a tile or two at a time and avoid over-aggro under the fog. It’s not harder, just more tedious. And even more self-defeatingly, Sacred Stones contains inexpensive consumable items and staves that can be used to illuminate the darkness up to several tiles away.

With that little critique of Sacred Stones’ combat mechanics out of the way, I want to come full circle and revisit the game’s support mechanics. Fire Emblem has rightly witnessed a huge surge in popularity in recent years and I attribute this largely to more polished intra-character interactions where players arbitrate not just death by the sword, but take major life decisions in general (who should X marry?). This has empowered players, giving them enormous auxiliary narrative control, who can use it to indulge their whims and make each playthrough narratively unique. Looking back, Sacred Stones’ its support system feels a tad primitive.5If 15-odd games over some ~30 years isn’t enough to polish a formula to perfection, then I don’t know what is.

In Sacred Stones, support conversations take place on battle maps and not, as one might expect, in a campsite setting. Active combat is a strange backdrop for light conversation, and it can be frustrating to sit through character X waffling on about his pet parrot while you’re in a tactical combat mindset trying to save your wizard-in-training from a pair of archers that showed up out of nowhere.

Friendship mechanics are implemented a little differently, too. Rather than establishing rapport by completing missions together (such as in Awakening), support score hinges on the number of turns that two units spend adjacent to each other. When a certain threshold is reached, a support conversation unlocks. This is an interesting system.. And it can be gamed mercilessly. Since enemies are stationary unless you seek them out, and there isn’t a mission timer, it is possible to form a support circle-jerk donut in a quiet corner of the map and just… Wait. Hit end-turn for a hundred-ish times and presto, each duo hits A-rank familiarity. This bestows some wicked permanent stat and combat bonuses whenever both moieties enter a mission together.

Rumour has it that Intelligent Systems rushed out the game on GameBoy Advance to predate the imminent release of the Nintendo DS, and having gone through most of the content, that seems likely. The cornerstone of all Fire Emblem titles is outstanding writing that manifests in a relatable, intriguing story with compelling characters – an area where Sacred Stones comes up short. Factor in decidedly mediocre tactical combat and the resulting product is sub-par by the series’ lofty standards.

All in all, playing Sacred Stones was a fascinating experience. Identifying its many gameplay experiments made for a journey of discovery that, to some extent, stood in for the journey of discovery I expected the game’s narrative to be. Looking back, Sacred Stones is clearly a title full of growing pains on Fire Emblem’s way to bigger and better things. And if you are seeking to play a classic Fire Emblem title for the sake of pure enjoyment only, I recommend Gamecube’s Path of Radiance over this one. However, If you have a few bucks to drop, and are looking to sample Fire Emblem’s humble roots, you could do worse than try out Sacred Stones on Wii U’s Virtual Console, or whatever emulation platform the Switch may eventually harbour. Just don’t expect much of a challenge.

- Harvest Moon 3 (2001) - March 5, 2020

- Pokémon Trading Card Game 2 (2001) - February 5, 2020

- Yu-Gi-Oh! Dark Duel Stories (2002) - January 5, 2020