They say that the only certainties in a human lifetime are taxes, death… And the annual theatrical release of a new Pokémon animated film! It all started with 1998’s Mewtwo Strikes Back. Twenty-odd movies have followed since – pictures in which protagonist Ash has been crushed, petrified, eaten alive, desouled, drowned, frozen, and incinerated, only to be revived over and over and continue his everlasting adventure. Hmm. Perhaps death isn’t inescapable after all. Ah… Such weighty issues! Pokémon was much simpler when all of its essence could be distilled down into an Exeggutor… Ooooddish!

Now, the Pokémon franchise delights in celebrating its milestones, and the arrival of Movie 10 – 2007’s Dialga Vs. Palkia Vs. Darkrai – was no exception.1 Known as The Rise of Darkrai in the West. Some of the hubbub surrounding the movie stemmed from the tenor of the film itself and the new ground it broke: the first in the Diamond & Pearl era, it featured uncharacteristic clash of titans monster movie-like scenes between the deities Dialga and Palkia, and moreover saw the first appearance of titular nightmare Pokémon Darkrai, which in a delightfully quintessential GameFreak feat of ingenuity made its concurrent silver screen and video game debuts (here). But there was equally a clear commemorative prong to this buzz, which sought to celebrate the fact that the franchise had succeeded in reaching its tenth movie jubilee at all.

As such, in the lead-up to Movie 10, The Pokémon Company (TPC) mounted a months-long “Pokémon Tenth Film Anniversary Commemoration” (ポケモン映画10周年記念) promotional campaign commanding much media attention and comprising an array of special merchandise. In this very Pokémonesque bid to celebrate the journey as well as the destination, older movie protagonists like Mewtwo, Lugia, Celebi, Jirachi to name a few were given plenty of love. And it was in this context that, by popular choice, the first of the older Mythicals made its grand entrance into Sinnoh.

As such, in the lead-up to Movie 10, The Pokémon Company (TPC) mounted a months-long “Pokémon Tenth Film Anniversary Commemoration” (ポケモン映画10周年記念) promotional campaign commanding much media attention and comprising an array of special merchandise. In this very Pokémonesque bid to celebrate the journey as well as the destination, older movie protagonists like Mewtwo, Lugia, Celebi, Jirachi to name a few were given plenty of love. And it was in this context that, by popular choice, the first of the older Mythicals made its grand entrance into Sinnoh.

Let’s take a look at Anniversary “10th” Deoxys.

—

Ten movies, and thus a decade of animation and film music. While the arrival of Movie 10 didn’t invite nearly as much fanfare as did the 2006 10th Anniversary of the Pokémon franchise as a whole, there was certainly no shortage of initiatives to take pause and commemorate. Take, for example, the temporary Pokémon exhibition put together at Tokyo’s Suginami Animation Museum, which looked back at a decade of Pokémon animation through production materials such as screenplays and movie merchandise as well as offering interactive “participation corners”. Or the “PikaLive” (「ピカチュウ・ザ・ライブ」) movie concert held in Tokyo on August 7, 2007 that sought to “revive memorable scenes along with movie music such as the theme songs”.2“みんなの思い出に残るあのシーンやこのシーンが、主題歌など映画で使われた音楽とともにコンサートでよみがえります!!”3Perhaps inevitably so, given how compositions and music in general were very expressly a major constitutive component of the core Pokémon experience from the Very beginning. See also Concert Chatot. Or this commemorative exhibit at the Yokohama Doll Museum!

Hot on the heels of Movie 10 followed limited edition anniversary merchandise, such as this gorgeous two-part complete DVD Box with Pikachu’s countenance printed on the side. But besides a predictable array of merchandise with the stylised figure “10th” slapped onto it, TPC also leaned heavily into promoting Pokémon protagonists of past movies. A rich theme practically begging for collect-’em-all anthology sets of… stuff, TPC released and/or endorsed an impressive range of goods.

Convenience store chain 7/11, for instance, began to carry a surprisingly high-quality figurine lineup consisting of twelve movie Legendaries and Mythicals (plus Pikachu) available as bottled drink purchase gifts. Branded the “Pokémon Figurine Museum”,4“ポケモンフィギュアミュージアム” if completed, buyers could look forward to receiving a complimentary pale blue storage trunk bearing Pikachu’s likeness. (See here and here for example; official page here.) Cinemas that were to screen Movie 10 sold a twelve card promotional Pokémon TCG set comprised of those same Pokéstars of yesteryear. And then there was this somewhat bizarre collection of Moncolle finger puppets…

No anniversary celebration could truly be considered complete, however, without a dedicated event Pokémon to help mark it! But which? While players would unquestionably have loved to get their hands on a full complement of Legendaries and Mythicals from PokéCenters for use in their copies of Diamond & Pearl, it’s safe to say that releasing a full anthology was for reasons logistical, technological and presumably commercial not quite a realistic option for GameFreak. How, then, was the company to decide which of the many first-decade exclusives to give out? Why, by letting the public choose, of course!

Enter the “Pokémon Popularity Contest” (ポケモン人気投票) that pitted yesterday’s stars of Mewtwo, Lugia, Entei, Celebi, Latios and Latias, Jirachi, Deoxys, Mew and Lucario, and Manaphy against one another in a winner-takes-it-all election. A Pokemon.co.jp contest page went up in early February 2007 that encouraged fans to cast their vote in support of their favourite Pokémon protagonist of all-time. The polls opened February 15 – four months ahead of Movie 10’s premiere – with a two-week deadline of February 28. Votes could be cast online on pokemon-movie.jp, at the Daisuki Club portal (shielded behind a login page on pokemon.co.jp) or, alternatively, readers of manga magazine CoroCoro Monthly could submit their vote via a postcard included in the March 2007 issue. Of course, CoroCoro supported the initiative with higher quality publicity than a mere postcard. As was the magazine’s wont, it expounded on the what’s what of the Popularity Poll in a colourful and visually spectacular fold-out feature piece. (Which also instructed readers to thumb over to p.46 of the issue and learn Eigakan Darkrai‘s secrets.) 5Five total participants in the vote stood to win a Nintendo Wii; another 100 won tickets to a special advance screening of Movie 10. The winners were announced two months later, in CoroCoro’s May issue. Finally, all sources explained, the most popular Pokémon was to be “distributed to Pokémon Diamond and Pearl as a special Advance Ticket bonus for this year’s movie!”6Full quote is: 「ポケモン映画10周年を記念して、2007年の劇場映画の特別前売券の特典のポケモンを人気投票で決定するよ。これまで公開された全9作の映画のタイトルとなったポケモンの中から、欲しいポケモンを選んで投票しよう。1番人気を集めたポケモンが、今年の映画の特別前売券の特典になって、ニンテンドーDS「ポケットモンスター ダイヤモンド・パール」にプレゼントされるよ!」

We can assume that this Popularity Poll caused a bit of a stir. This was, after all, fans’ first-ever opportunity to collectively decide on a Pokémon for event distribution. Publication Famitsu quickly picked up on it, as did DengekiOnline. Yet despite this one-off, unprecedented chance, there were – as far as I can tell – no desperate messageboard persuasion pitches nor, in fact, was there any attempt at online coordination to get a particular favourite elected. Why this was so, I’m not really sure. Perhaps Japanese interwebbers were still to discover the possibilities of social media poll manipulation. It certainly is true that that the Popularity Poll pre-dates the astonishing victory of Magnemite over Legendaries such as Giratina in a 2008 Japanese Pokémon wallpaper contest (e.g. here), which is oft-cited as the first instance of Pokésphere digital vote rigging. (Incidentally, who remembers 4chan sending Justin Bieber on a tour of North Korea? Good times.)

As February rolled over into March, pokemon.co.jp put up a placeholder “suspense page” that teased the results, but did not yet provide them. Then finally, on March 15, 2007, the website raised the curtain: the greatest number of votes had been received by Deoxys, star of 2004’s film Destiny Deoxys.7The publication date of March 15 suggests a synchronous announcement printed in the April issue of CoroCoro; I’ve not been able to locate images of the pertinent pages. We can see from the Wayback Machine’s archival snapshot that this announcement incorporated a multitude of images and/or infographics which, we might assume, revealed poll statistics such as the total vote count and/or the vote share by Pokémon. However, crawlers did not (get to) pull these in. Surviving contemporary personal blogs did not reproduce them, and though media outlets such as InsideGames reported on Deoxys’ victory, they did not include said pictures either. The graphics therefore sadly appear lost to time. It can only have been a contributing factor that the raw results page didn’t stay live for very long: within a week or two, the URL’s content was again replaced, this time by a more extensively promotional message singing the praises of this freshly announced 10th Deoxys and, not unimportantly, giving details on how to acquire it!

Which was, as noted a few paragraphs back, from a special voucher included with Dialga Vs. Palkia “Advance Tickets” (前売り券). Now, the concept of parting with one’s money early in exchange for a supplementary event Pokémon was hardly novel. In fact, franchise patriarchs first conceived of the idea in the aftermath of 2003’s Pokémon Heroes: Latios & Latios, when flagging public interest had manifested as a sharp decline in cinema viewership and, in hopes of drumming up publicity, rekindling fans’ passion for seeing Pokémon in theatres, and boosting revenue, they moved to slap a thematic bonus “Negaiboshi” Jirachi on Advance Tickets the year after. Pokémon execs duly noted an immediate increase in sales: a spike so prominent that Mr. Satoshi Senda (former Managing Director of Toho) is on record as crediting Jirachi – Wish Maker Advance Tickets with initiating a “V-shaped recovery” in movie attendance.8Movies 6, 7 and 8 featuring Jirachi, Deoxys and Mew (the latter two with Aurora Ticket Deoxys and Hadou Mew as bonuses) all went on to earn in excess of ¥4 billion (~40m US$) at the box office, compared to <¥3bn for 2003’s Pokémon Heroes: Latios & Latios – the last film without an advance ticket bonus. To put these words into context: A whopping 1.75 million Advance Tickets sold for 2005’s Lucario and the Mystery of Mew; this on a total Japanese population of some 125 million. That’s impressive.

All this is to say that by 2007, Advance Ticket special vouchers could rightfully be called a staple of the event Pokémon landscape. Unlike predecessors Negaiboshi Jirachi, Aurora Ticket Deoxys, and Hadou Mew, however, the democratically chosen Advance Ticket 10th Deoxys had bugger-all to do with the substance of the movie. Fans, however, didn’t seem to mind this slight incongruence. Nor did they worry that Deoxys needn’t have been a paid-for Advance Ticket bonus at all: it could just easily – and appropriately – have been handed out as a costless PokéCenter commemorative wireless gift!

In any case, excitement prevailed as Advance Tickets went on sale April 21, 2007. Of course, TPC left nothing to chance and pushed early adoption hard – the updated website displayed a ticket hotline phone number quite prominently, and month after month, the pages CoroCoro Monthly were filled with extensive movie coverage. Early indications, then, were that Movie 10 advance sales would exceed the benchmark set by Lucario and the Mystery of Mew, with already 500,000 tickets sold by May 13.9Source is: https://nlab.itmedia.co.jp/games/spv/0705/14/news044.html

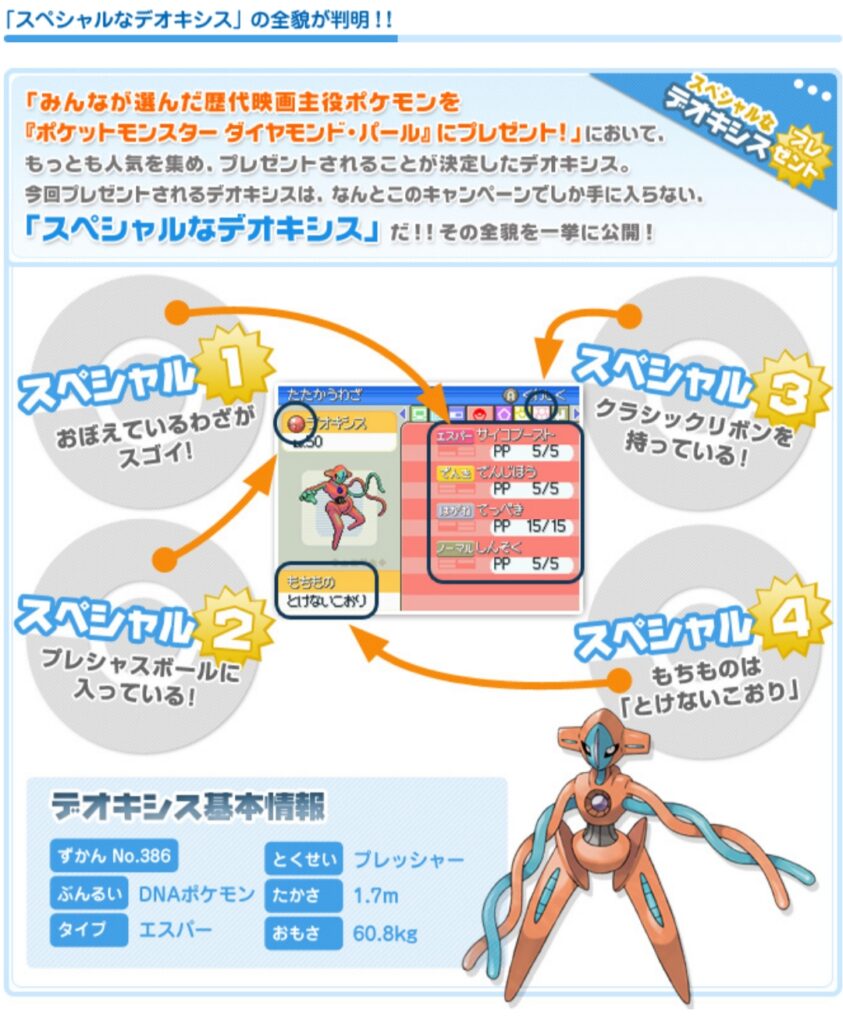

Any misgivings people might have had about an undercurrent of naked commercialism quickly melted away with the emergence of 10th Deoxys’ particulars, which revealed an intriguing and well-designed event Pokémon. It appears that GameFreak understood full-well they were delivering an unusually impressive product, not least evidenced by a gigantic infographic on the official website unabashedly titled “Special Deoxys Fully Revealed”.10「スペシャルなデオキシス」の全貌が 判明!! Not only was this to be the first Deoxys native to Gen 4, it possessed four noteworthy traits. As its creators were eager to highlight through bullet points, this Deoxys had a “Special” (1) Moveset, (2) Cherish Ball, (3) Ribbon, and (4) Held Item. Of course, CoroCoro Monthly drove these points home as well, running a full-page Deoxys special in its May 2007 issue, and again in the June 2007 supplementary “Darkrai Perfect Guide Book”.

Deoxys promotional page, “Darkrai Perfect Guide Book”. Supplement to CoroCoro Monthly, June 2007. Author’s collection.

In actuality, some of these bullet points were only quasi attention-grabbing. The event-exclusive Cherish Ball was certainly uncommon but not unique: the widely available “Sunday Specials” of Shokotan Tropius and Yamamoto Whiscash had also come in them several months prior (Feb-March 2007). More so, Cherish Balls would rapidly become the standard Pokéball of choice for high-profile Sinnoh event distributions. And while Deoxys’ Classic Ribbon was a nice touch, it could hardly be considered a selling point. In fact, the ribbon’s most profound implication was that it helped protect GameFreak’s commercial interests surrounding the film. You see, ribboned Pokemon were by default untradeable on the GTS, meaning that authentic Deoxys (plural) could therefore not be mass-cloned then bartered off, which might otherwise reduce recipients’ desire to purchase Advance Tickets of their own (¥1300)!

Rather, Deoxys’ defining properties were easily its striking moveset and reverential nod to Movie 7 in the shape of its held item, a Nevermeltice. Let’s start with the former. You may be aware that any Deoxys can assume four possible “Formes”. In Generation Hoenn, a Deoxys’ active Forme correlated with the specific video game it resided in. For example, a Deoxys freshly caught off an Aurora Ticket in Ruby & Sapphire would be in “Normal Forme”. If a player transferred it to remastered version Emerald, it would automatically take on Speed Forme. And if the player were to migrate it to Kanto remakes FireRed or LeafGreen, it would take on Attack Forme and Defense Forme, respectively. Each Forme had a different base stat distribution, recalibrated on transformation in accordance with – as the Forme names imply – their respective tactical roles. Furthermore, each Forme had access to several exclusive moves that, if learned, were retained on shifting shape. Altogether this represented fantastically creative game design on GameFreak’s part, resulting in an endlessly customisable, exotic Mythical.

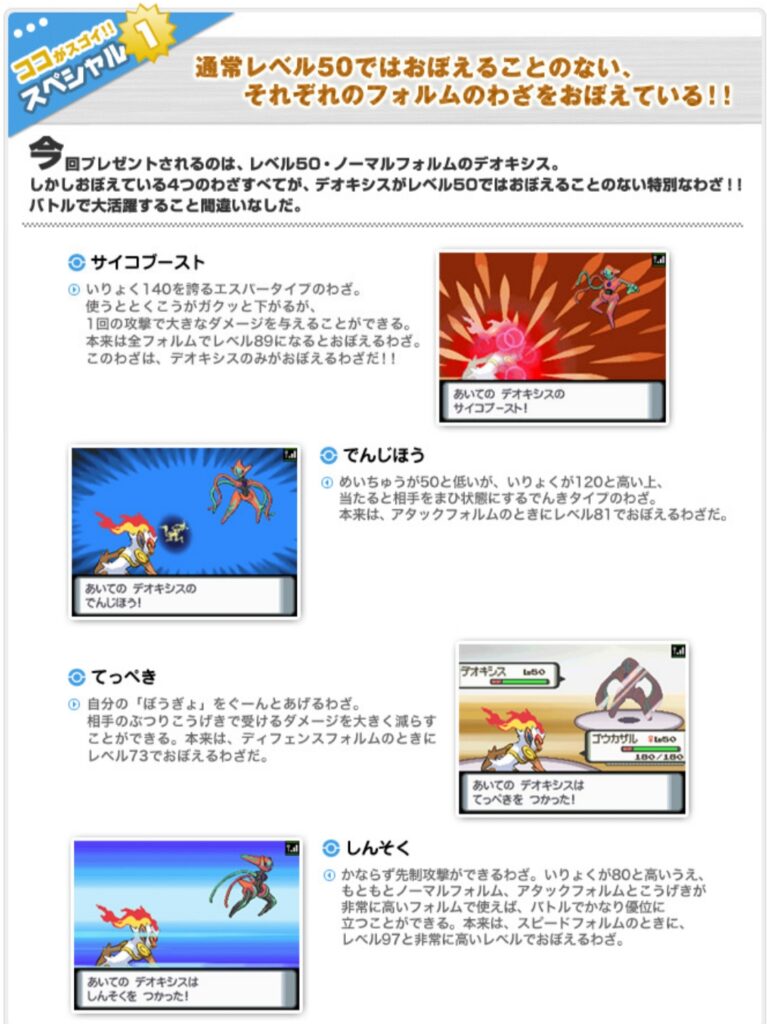

Brilliantly, 10th Deoxys knew a predefined combination of advanced Forme-specific moves out of the box. Despite being distributed at Lv.50, it packed Psycho Boost / Zap Cannon / Iron Defense / Extremespeed – moves it wouldn’t normally learn until Lv.55 (Iron Defense), Lv.61 (Zap Cannon), Lv.67 (Psycho Boost), and Lv.73 (ExtremeSpeed). While none of these attacks are mutually exclusive on any Deoxys (as are, for instance, Zap Cannon and Recover), the composition of 10th still saved players a lot of Forme juggling to build a competitive Deoxys. For GameFreak very much designed 10th Deoxys with competitive battling in mind: so much so that they prepared a second infographic just to drive home the point that it knew its four moves far ahead of the normal levelling curve and to elaborate on the raw power and synergy of its moveset. “There is no doubt that it will be a big success in battle”, the image read.11“バトルで大活躍すること間違いなしだ”

For players who wanted to customise and tailor Deoxys to their needs anyway, Diamond & Pearl had them covered. Unbeknownst to practically anyone but the most inquisitive of players, Diamond & Pearl (D&P) incorporated an inconspicuous clandestine Deoxys Forme transformation facility. If you’ve played the Sinnoh games at all, you may recall the presence of a trio of interactable meteorites on the outskirts of Veilstone City. Well! If any of these is approached with Deoxys in the front slot of the player’s party, it provokes a Deoxys Forme change! See this tastefully antique video for a demonstration. While applicable also to Aurora Deoxys migrated upwards from Hoenn, these space rocks’ hidden mechanics became so much more pertinent in the wake of 10th Deoxys’ release. It’s frankly impossible for GameFreak to have foreseen that the general public would elect Deoxys – heck, it’s improbable that the tenth film anniversary commanded any sort of special consideration during Diamond & Pearl’s development. That the meteorites, then, were in the games at all, thus preparing D&P for this eventuality, is testimony to exceptional levels of genuine care, forethought and sense of purpose that GameFreak poured into these titles.

Now, perhaps the coolest thematic touch of 10h Deoxys – quite literally so – came with its held item, a Never-Melt Ice. This cube is not particularly useful competitively, where it boosts the power of Ice types moves and is rarely used on Deoxys, deferring to Focus Sash as go-to item to compensate for the DNA Pokémon’s extreme frailty. Rather, the Never-Melt Ice was a clever and somewhat oblique reference to Movie 7: Destiny Deoxys. As the official distribution page explained, in that film, Deoxys emerged from a meteorite that crashed into a large polar ice field. “In connection with this appearance scene, the presented ‘Special Deoxys’ holds a ‘Never-Melt Ice’!”12Full quote is: “デオキシスが主役を飾った2004年公開の「劇場版ポケットモンスターアドバンスジェネレーション裂空の訪問者デオキシス」で、大氷原に激突した隕石から現れたデオキシス。この登場シーンにちなみ、今回プレゼントされる「スペシャルなデオキシス」はどうぐ「とけないこおり」を持っている!!”

Now, perhaps the coolest thematic touch of 10h Deoxys – quite literally so – came with its held item, a Never-Melt Ice. This cube is not particularly useful competitively, where it boosts the power of Ice types moves and is rarely used on Deoxys, deferring to Focus Sash as go-to item to compensate for the DNA Pokémon’s extreme frailty. Rather, the Never-Melt Ice was a clever and somewhat oblique reference to Movie 7: Destiny Deoxys. As the official distribution page explained, in that film, Deoxys emerged from a meteorite that crashed into a large polar ice field. “In connection with this appearance scene, the presented ‘Special Deoxys’ holds a ‘Never-Melt Ice’!”12Full quote is: “デオキシスが主役を飾った2004年公開の「劇場版ポケットモンスターアドバンスジェネレーション裂空の訪問者デオキシス」で、大氷原に激突した隕石から現れたデオキシス。この登場シーンにちなみ、今回プレゼントされる「スペシャルなデオキシス」はどうぐ「とけないこおり」を持っている!!”

On July 1, 2007, nationwide delivery of Deoxys commenced. As usual, it was available from seven physical PokéCenter stores across the country as well as three Pokémon Towns. Now, because 10th Deoxys concerned an exclusive Advance Ticket bonus, “slot-2” distribution with manual customer verification was the only delivery option; and because slot-2 distribution was practically mandated, there arose, unavoidably, lengthy queues of customers lining up, single file, for hours on end waiting to be serviced. If you’re unfamiliar, so-called “slot-2” distribution was the Sinnoh era’s direct method of delivering an event Pokémon, accomplished by jacking in a dedicated distro device to the second (GBA) slot of the presenting player’s Nintendo DS while Diamond or Pearl was running, thus allowing a manual wondercard (WC) transfer via Mystery Gift. It goes without saying that this method was time-consuming, since each customer needed to be serviced by staff individually, whereas wireless distribution (as used for early 2007’s Sunday Specials) was entirely hands-off. Queues tended to form whenever slot-2 distribution was used, as was very notably the case for PokéFesta Magmar & Electabuzz and Water Tribe Manaphy at the turn of the year.

Players were fortunate in that they could pick up 10th Deoxys and 2007’s edition of Tanabata Jirachi [LINK] concurrently and kill two birds with one stone, thus necessitating only one PokéCen trip marred by much standing around and waiting. Bloggers like Kei85 (here) and Dekohachi (here) exercised this option. While the former detoured to PC Tokyo on a weekday nearish the end of Jirachi’s distribution window and found their path unobstructed, Dekohachi – arriving on Sunday July 1, Deoxys opening day – discovered a “great procession”. Dekohachi ended up queueing for three hours (!) in a combined Deoxys-Jirachi line, during which time they “talked with parents and children in the same line and traded” and “had a good time playing.” That doesn’t sound so bad! More broadly, even though we understand that Deoxys delivery was a large-scale operation – documentation by the ever-dependable Pikachuftt suggests that a minimum of 726 (!) Deoxys distribution carts was manufactured – the sheer volume of commited customers inevitably meant that PokéCenters were both swarmed and swamped.

Which, of course, was a natural reflection of the immense quantity of Movie 10 Advance Tickets purchased by the public. Early indications of record-breaking numbers had been correct: total Advance Ticket sales topped two million as fans proved massively hungry for Deoxys. “There were people who bought many Advance Tickets because they wanted Deoxys”, observed blogger oko-bou as they commented on the film’s commercial success. Fellow writer encalyptus was one of them, reporting on their purchase of five adult tickets primarily to secure all five movie poster variants, though they couldn’t help but underscore the exciting prospect of grabbing five 10th Deoxys for themselves.

With millions of Poké-mad Diamond & Pearl players in Japan, a portion undebatably bought Advance Tickets solely because of the bonus Deoxys. If nothing else, this is borne out by those avid fans prepared to shell out money on multiple tickets just to get multiple Deoxys, though as a whole, we can assume this contingent was small. Enticed by Deoxys, others may have gotten tickets sooner than they otherwise would have (ie. not made advance purchases). For yet others, the draw of combined Deoxys and Darkrai distributions may have been sufficient to pull them across the line and see a film they otherwise might not have. And finally, we can equally assume that for many nothing changed, for they would have gone to see the film anyway!

Whatever motivations they tapped into, by 2007, Advance Tickets had earned their stripes as both a fiscally attractive proposition for TPC and a beloved part of the Pokémon event landscape for collectors and casual fans alike, and they would continue to be employed throughout Generation Sinnoh and beyond with Regigigas to Shaymin, Shokotan Pichu to Arceus, and so on. But all that was still years away. By late Spring 2007, only one Pokémon dominated Poké-headlines: Darkrai.

For the story of Cinema “Eigakan” Darkrai, see here!

- Harvest Moon 3 (2001) - March 5, 2020

- Pokémon Trading Card Game 2 (2001) - February 5, 2020

- Yu-Gi-Oh! Dark Duel Stories (2002) - January 5, 2020