Final Fantasy V: the Super Nintendo game that never was. Not in North America and Europe, at least. Concerned that the unprecedented complexity of its gameplay systems would turn off Western audiences, developer Square opted against a worldwide release for the game, thus confining Bartz, Lenna, Galuf and Faris to the Japanese islands until the 5th anniversary of their adventure.

In the gaming hive-mind, Final Fantasy V (FFV) is remembered for dust-binning the hardlocked, immutable character classes that had theretofore dominated role-playing adventures. Instead, FFV introduced a system of “jobs” – or interchangeable character specialisations – to reinvigorate an ageing and increasingly stale turn-based combat formula. Featuring a total of 22 specialisations, from Dragoon to Summoner to Dancer, all with special abilities transferable between classes, FFV permitted an outrageous level of character customisation for the era.1Technically speaking, FFV took a leaf out of Final Fantasy III‘s book for NES, which had already experimented with interchangeable professions, albeit to limited scope and mixed success. This daring formula hit the ground running in Japan, where Final Fantasy V sold over two million copies.

In the collective consciousness of history, however, Final Fantasy V’s status is closer to forgotten middle child sandwiched between the stately FFIV and surrealist juggernaut FFVI, and seldom celebrated as milestone accomplishment in its own right It’s not difficult to discern multiple causes. First, FFV’s want of a Western release restricted Occidental engagement with the game to eyeballing glossy screencaps in gaming digests. Can’t don nostalgia-tinted glasses for a game you’ve never played! Moreover, successive Final Fantasy titles shelved the fine-tuned freedoms of character specialisation, removing the possibility for throwback and hurting any immediate legacy FFV might have had. For over a decade, then, FFV remained an oddball package of RPG experimentality, a relic of an era when developer budgets were smaller and studios bolder.

Neither of those factors are nails in the coffin of enduring popularity, though. Mother 3 never saw a Western release, but nonetheless sports a cult following to rival any Tim Schafer adventure game. And the Tactics Ogre-series only forayed into grand strategy once with March of the Black Queen, yet we regard that title with unfailing reverence. No, I think the fundamental reason why even today Final Fantasy V is not held in remotely equal esteem to its bookend siblings2Although FFV recently caught the eye of Kotaku’s Jason’s Schreier, who gave it a little bit of overdue love. despite multiple re-releases in English is because – for all its mechanical prowess – FFV‘s storytelling is simply abysmal. From the crude presentation of its central conflict to bland personalities to an unsatisfyingly shallow wonderland, Final Fantasy V executes its narrative and creative beats in remarkably primitive fashion, putting a damper on the entire experience.

But hey, let’s play nice and home in on the bright spots first. Including – ahum – the not altogether improbable occurrence of protagonist Bartz waltzing across the battlefield in decidedly effeminate Dancer costume.

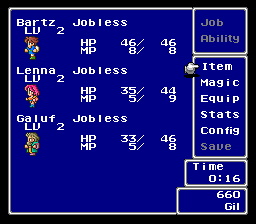

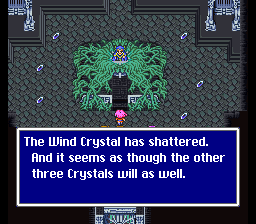

As in Final Fantasy III for NES, Team Bartz begins the adventure as Freelancers, or “Jobless” in the RPGe translation I played (is there a difference in this day and age?): code for plainclothes brawlers that impassively punch monsters in the mouth. However, when the sacred Wind Crystal unexpectedly shatters during FFV’s dramatic opening hour, its fragments mysteriously levitate towards the Heroes of Light to endow them with the strange ability to assume several combat professions – from Knight to Thief to White Mage. Each additional Crystal that crumbles to smithereens over the course of the adventure expands the selection of professions into increasingly niche and arcane specialisations such as the Mystic, the Dancer, the Berserker and the almighty Summoner. Some professions are clear-cut power-hitters; others excel at support or have a variety of unique tricks up their sleeves. Moulding characters at whim to the vision in your mind’s eye is exciting, and the game fully facilitates this by freely allowing job-switching: anyone can be anything at any time.

There’s a catch, though. For a character to master a specialisation, Ability Points (ABP) must be obtained from defeating enemies in battle. ABP accrue to whatever “job” a character occupies at the time to gradually unlock secondary abilities that, brilliantly, are transferable across primary professions. This makes it possible to, say, create a White Mage with the bare-fisted punching power of a Monk, or a Knight that invokes reality-bending Time Magic to double the frequency of his, or an ally’s, attacks. More powerful abilities are gated behind higher job ranks that can require hundreds of ABP to attain, which translates to – you guessed it – hundreds of random encounter victories. That’s fine considering the *cough* generosity of FFV’s encounter rate, but it does mean that sticking to a broad-strokes specialisation plan is essential to avoid tedious course-correction later on.

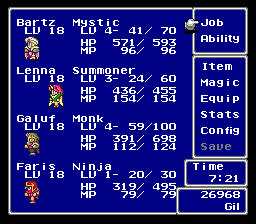

Generally I like this system quite a lot. Messing with job combinations is fun and FFV serves up just enough challenge in boss fights to make optimisation meaningful and worthwhile. Team composition really does matter. For example, I failed miserably at defeating Esper Shiva with a pair of unassuming Knights, a dedicated Monk, and a fragile White Mage. Without resorting to any sort of grinding, I tweaked my job assignments and positively trounced her with a dual-wielding Mystic, a Sylph-invoking Summoner, and that same hard-hitting Monk, all fuelled by the power of Haste courtesy of pirate Faris in pointy Time Mage attire.

It seems incredible now, but packing so many degrees of freedom into a videogame was boldly complex for 1992. (So bold, in fact, that Square rejected a Final Fantasy V Western release for fear the game’s depth would mystify its prospective player base – as mentioned in the introduction). Twenty-five years down the line, however, and I’d wish Sakaguchi & co had dared venture even further beyond FFIII. What I mean is this.

Obviously, the job system permits the transfer of creative capital traditionally the prerogative of game developers to the player, thereby also transferring a degree of ownership of the story’s main characters. It goes without saying this design philosophy was progressive; even today, while most games readily present a plethora of (combat) specialisation options through a tech-tree, they seldom allow you to redefine a character’s combat role or class entirely. FFV’s seldom-seen flexibility to completely overhaul any character at any time is without question among its greatest claims to fame.

Yet if you care about the numerical fine print, it is possible to find in Final Fantasy V’s main cast the echoes of the class fixity present in predecessor Final Fantasy IV. On the surface FFV’s characters are indeed tabula rasa, but even so, from the SNES original to the 2006 GBA re-release, the base stats of Bartz, Lenna, Galuf and Faris predispose each of them to a narrow range of classes. Bartz and Galuf pack superior physical strength, Lenna is magically gifted, while only Faris sports a base evasion of 10%. Throughout the game this weighted growth continues regardless of the job(s) you assign, as patterns of stat growth are inalterable. It’s as though Sakaguchi’s team, intimidated by the terro incognita in which they found themselves, sailed back to home port rather than venture deeper into the unknown.

Of course you’re free to ignore each character’s innate talents if you can settle for sub-optimal use of your party members. But if you respect these predispositions as reflecting the creators’ vision for Final Fantasy V, then a cross-cut of optimal classes is locked in for each character from the outset.3Granted, many viable combinations remain, but if you’re at all like me you’ll never permanently shoe Lenna into a physical class if someone else fits that bill better, just like Faris will never specialise in a job that doesn’t exploit her evasion to the hilt (e.g. Thief or Ninja). I find this uncomfortably at odds with the wider spirit of FFV, whose founding philosophy is the class flexibility that I have been touting in this retro-review, and that saw Square kill an overseas release.

This vestigial fixity, this reluctance to fully embrace the unknown – it strikes me as an unbelievable pity and missed opportuntiy at that. Imagine if FFV had gone all-in and not only removed character predispositions but opted for job-based stat increases, whereby a Knight, for example, would logically gain high strength, defence and HP upon level-up but suffer mediocre magical growth, while a Black Mage would sacrifice physical stat growth in return for increases to magical prowess. This is, of course, a time-tested system harnessed by other games of the era and beyond, including Tactics Ogre’s March of the Black Queen and Knight of Lodis and – so I’m told – Final Fantasy VI. Implementing it in Final Fantasy V would allow for the creation of shades of a particular profession that forego one attribute for another and effectively extend the job system’s core philosophy of offering unprecedented playstyle flexibility.4And when level-up is imminent, one could class-switch to bank the stat increase aligned with your vision for that character, while still retaining the flexibility to class-change for specific battles. It could co-exist readily with other aspects of the job system such as ABP-based growth and secondary skill transfer, necessitating no other changes to extant game systems.

If the choice were mine, I’d even consider going one further: transfer control of stat-growth to the player by allowing us to freely allocate a tally of points to any stat upon level-up (such as in Square’s Super Mario RPG). Want to spurn Bartz’ defence to manufacture a textbook glass cannon? That’d be perfectly viable, particularly if combined with a shield-bearing, high-def ally rocking the “Cover” ability. Or what about moulding Lenna into a Summoner who sacrifices physical offence for steely defences and magical aptitude? I would love to customise FFV this way. It would force advance character planning in the style of Tactics Ogre, and it would make every playthrough positively unique.5If that’s too hardcore for you, a Borderlands-style respec option could serve as get-out-of-jail-free card. Any modders out there who can do this?

—

Right, so let’s leave behind the job system and consider areas where the Final Fantasy V experience is a leaky bucket – the most sizeable hole in this receptacle being, as you’d expect from the intro, the story.

FFV’s opening act sees a gallant King Tycoon gazing skyward from his castle’s balcony, beset with doubt and apprehension, sensing an ominous change in the winds. His intuition soon proves correct, for moments later a giant meteorite crashes into the earth, leaving behind an enormous impact crater. Three heroes are drawn to the site of this cataclysmic event: Bartz, roving loner with a Chocobo as his steed; Lenna, lissom princess of Tycoon; and Galuf, an amnesia-riddled buffoon clearly of noble blood. After a chance meeting, all resolve to investigate the integrity of the Wind Crystal together, whose fate somehow – inexplicably – seems intimately entwined with the spacerock. En route they collect Faris, lady captain of a pirate band, and so with a minimum of fanfare in the space of 20 minutes the Fantastic Four are assembled to sustain you for the next several dozen hours.

It isn’t long before we learn of the existence of four Shrines total, erected across the far reaches of the known world, and each home to an elemental Crystal that is, like the Wind Crystal, also inexplicably but assuredly at risk of shattering. The objective for game is thereby set: travel to each of these locations, prevent – if at all possible – its Crystal breaking up into a million pieces, and if not, deal with whatever evil arises as a result. Within the hour, all of Final Fantasy V’s cards are on the table.

The setting, then, is standard fantasy, and the premise a little uninspired. That’s fine though. Not every game needs a message; many JRPGs have stock premises that come to life through clever writing. Besides, devising a compelling overarching story with appropriate hooks and pacing and conclusion is tough. Playing it safe plot-wise to narrate a simple story to perfection is a perfectly viable path to success; not every RPG needs to be Nier: Automata.

But… FFV’s simplicity is seldom compelling. Final Fantasy V’s script is remarkably pithy for a fully-fledged RPG, using few words to say even fewer things. Its attempts at humour rely on slapstick and visual comedy. Worse, FFV tries to compensate for the dearth of character- and world-building by falling back on soapy drama, but does so in the most haphazard fashion conceivable to create a total want of credible suspense. It is emblematic of Final Fantasy V that there is little build-up or foreshadowing in the way it constructs plot points, major or minor. Dramatic events constantly transpire at the drop of a hat and conclude on the spot with even greater swiftness. You think I’m exaggerating? I’ll give an example.

Early in the game Lenna heroically wades through a field of poison-string vegetation in order to retrieve a curative herb, Dragon Grass, that just happens to be growing mere yards from her mortally injured pet dragon, Hiryu, on some cloud-piercing mountaintop. Wasting no time, Faris successfully administers the herbal concoction to the dragon. Lenna, however, is severely weakened by floral toxins and collapses mere moments later. An instantly revivified Hiryu then shuffles over to Lenna’s unconscious body and, with extraordinarily sentience and tenderness for a gargantuan beast, applies its monstrous beak to whatever wounds Lenna sustained from the flowers – scratches from spiky vines, I assume – and siphons the venom right out of her.

No evidence of damage done, Lenna springs to her feet to immediately start jumping up and down with maniacal excitement. Galuf lets loose a signature bellowing laugh, Hiryu is declared insta-cured, and without further ado the adventurers fly off into the sunset on dragonback. From start to finish the entire scene in which a central protagonist nearly dies concludes in under a minute (46 seconds to be precise; I timed it). Before I could process just what I had witnessed, the game had moved on, oblivious to the narrative rush-job that left me scratching my head. (I had a similar experience watching Game of Thrones’ “Beyond the Wall” (S7E6) – articulated well by Erik Kain over on Forbes.)

This happens time and again. Where FFV should slacken its blistering pace to throw down compelling plotlines that structure the adventure and build up emotional stakes, it instead presents impromptu here-and-now drama of a hollow, mawkish, “that-just-happened” quality. This soap opera-like presentation keeps Final Fantasy V from developing the gravitas appropriate for an epic adventure and compromises the odd story arc that does span multiple Crystals.

Why-oh-why does Final Fantasy V fall so woefully short in the narrative department, more so than its siblings? Undoubtedly the job system plays a part, with its need for identikit characters that can don any hat, precluding the creation of in-depth personal backgrounds to anchor the story. Even accounting for this, however, it feels as though whoever penned FFV’s script laboured under a hard per-event word limit forcing exposition demanding thorough, delicate treatment into the bite-sized, corner-cutting storytelling of a promotional leaflet. Oddly, this may not be too far from the truth. FFV was banged out in only twelve months or so, making the journey from concept to release in remarkably short order; this may have forced early finalisation of the script, thereby prematurely locking-down the spartan writing of rough-and-ready draft versions.6Disclaimer: conjecture of the purest kind. Regardless, the product is a disposable overarching narrative too reliant on tacky, roll-eyes drama. It’s… Not great.

—

Whew. Okay. Now, I think that even a weak or concise premise can be salvaged through graphically rich, textually varied and/or event-packed location design. With Final Fantasy V set in the purest of Narnia’s, unbound by the physical rules of the natural world (it is called Final Fantasy, after all), there is plenty of scope to jam-pack it with marvels. For some time I indeed expected FFV to proffer tantalising discoveries round every next corner. Offering zero indication for why my party was travelling in any given direction at any given time beyond the obvious goal of tracking down the next Crystal,7Rarely are you steered towards a specific site in anticipation of resolving some kind of (sub)plot. FFV cultivated the impression of an intentional reticence to preserve the mystery of upcoming infinite wonders, ripe for discovery by the player. Think modern example Breath of the Wild, where – as in FFV – the very first quest you receive is also the final objective (defeat Ganon). It’s what happens in between that blows your mind multiple times over.

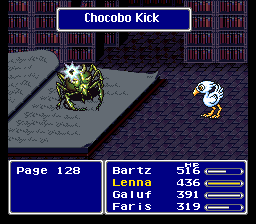

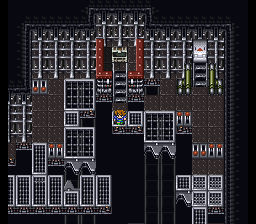

But while Breath of the Wild delivers on its promise of infinite marvels thrice over, Final Fantasy V makes too little of its wonderland. (It’s not a fair comparison, I know.) Of course there are highlights, such as the timed escape from Karnak Castle that turns into an impromptu race to collect a diffuse treasure hoard guarded by monsters (10 minutes to blow and ticking down!). The Ancient Library stacked with books possessed by demons also comes to mind, which is a wondrous, mildly horrifying product of an Edmund McMillen-like, if not outright Kafkaesque, twisted imagination. As do the cleverly laid out innards of Cid’s fire-powered ship, which require much switch-flicking to jolt into motion mechanical parts like floating platforms and one-way conveyor belts. Where FFV combines a cool cyberpunk aesthetic with light puzzling, the game is easily at its best.

But such unique environments, I think, are dotted too lightly throughout the adventure. Most locations on the map are graphically uniform, nondescript towns and castles that feel like mandatory stop-offs to replenish health and upgrade gear but otherwise lack surprises (or plot pertinence). Tailing the skeletal story, the concept of side-quests is alien to Final Fantasy V, missing an opportunity to flesh out its universe and protagonists – nay, to give the protagonists much of a personality at all. There is no such thing as lore snippets scattered around habitats in written form or from NPC anecdotes. Everywhere the gameworld is rote and skin-deep, giving the player – or me, at least – the sensation of passing through FFV’s universe rather than offering the tools for immersion. A good gameworld cocoons around you, swallowing you up with its personal version of reality; FFV doesn’t come close.

The glass half empty observation, then, is that FFV’s story-deprived, no-questions-asked railroading is evidently not a device for packing the world with a thousand-and-one wonders. FFV isn’t taciturn to preserve mystery, but because it has nothing to say. Like the adorable woof-woof Hachiko at Shibuya Station, for hours on end the player yearns longingly in anticipation of that flash of excitement, until this illusion eventually shatters, despondency sets in, and one must come to terms with the fact that, in actuality, nothing will come, and that the world’s voidness is just that… Much empty. Final Fantasy V presents a pro forma race to the finish with paltry surprises along the way.

And if that doesn’t damn an RPG, I don’t know what will.

If this decidedly mixed report card hasn’t dimmed your desire to fire up FFV yet, then you have a few versions to choose from. The SNES original patched to English using the 1990s RPGe fan translation is the purist’s choice. Fan forums speak highly of it. Personally, I think that while of undeniable historical significance – it is, after all, the first ever collaborative fan translation to English of a Japan-only RPG – you’ll need to don a pair of nostalgia-trimmed, rose-tinted spectacles to truly appreciate this one, as I find even the LoTC-corrected version somewhat crude by today’s localisation standards.8This is not to speak ill of the RPGe fan translation, which is commendably faithful to the original Japanese. (Rule of thumb: if Persona 5’s localisation didn’t rub you the wrong way – be faithful and play the SNES version.)

The 2006 Final Fantasy V English re-release for GameBoy Advance, on the other hand, is a licensed, more idiomatic localisation (not a mere translation) that not just irons out stenographic oddities like the triple exclamation marks and awkward line spacing carried over from the original Japanese, but, more importantly, retouches dialogues to strengthen character individuality and bring logical cohesion to the narrative – therein arguably exceeding the original Japanese.9And easily surpassing the questionable translation of the 1998/9 PS1 version. It’s not a panacea to FFV’s story ails, but every bit helps.

There’s also extra content, if you care for that: four new jobs (ft. the ghastly Necromancer), actual character portraits to support dialogues, an additional dungeon (with little bearing on the story), and a gentrified visual presentation. Critical as I am of FFV’s original SNES graphics which lazily upcycled the style of FFIV, I don’t consider the GBA’s presentation an improvement since its imaging is fairly low-res and scarcely an upgrade on detail. The overall package, however, benefits from the polish of hindsight, making it arguably more attractive than the original. Plus you’ll get a chance to experience FFV’s excellent soundtrack – courtesy of the legendary Nobuo Uematsu – on a marginally better sound chip. Go ahead, then; climb Hiryu’s Wings. And if you’ll take the plunge, you might as well do so between June and August (of every calendar year) and support charity’s Four Job Fiesta!