Have you played Tactics Ogre: The Knight of Lodis, the acclaimed strategy RPG from Quest? Chances are you’ve never come across it – Knight of Lodis (or KoL for short) was obscure in the West even on release. Incidentally, this rarity now puts it among the most expensive Gameboy Advance (GBA) titles on the market. Original boxed copies are scarce – beware the plethora of knockoffs on Ebay! – and can sell for upwards of $150USD. Undershooting demand was somewhat of a mainstay for publisher Atlus, anyway: only 25,000 copies of KoL’s prequel, March of the Black Queen for SNES, found their way to the US in the mid-90s. And the price of those, well… Why don’t you see for yourself.

But I digress. Atlus truly did RPG fans a monumental disservice by opting for an abysmally small print run. In my book, Knight of Lodis is far more deserving of the GBA ‘tactics’ crown than Final Fantasy Tactics Advance (FFTA), the commonly considered rightful recipient. KoL’s niche status certainly didn’t do it any favours: I had to hunt far and wide to locate an isolated copy even in the early 2000s even as every kid in the neighbourhood seemed to have Montblanc hopping across the GBA’s dimly-lit screen. FFTA’s staying power has been greater, too; one only has to search YouTube for Let’s Plays to appreciate its enduring legacy.

Even so Knight of Lodis is an incredibly rich, engrossing experience that has withstood the test of time exceptionally well, and is frankly hands-down the superior game. Above all, the captivating, gritty realism of KoL’s intrigue-packed plot sustains the experience from start to finish and lends cohesion and gravitas to every mission. But mechanically Knight of Lodis excels too, as its combat mechanics are dynamic, intuitive and well-calibrated while class progression and character customisation are smooth and organic – a far-cry from, say, the FFTA Ability Point grindfest. Taken together, the game is hard to put down, even 15 years after release.

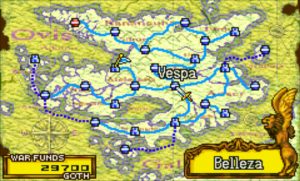

Our story starts in Ovis, a sizeable island parcelled into the self-ruling state of Rananculus in the north and Anser, client-state of the expansionist empire of Lodis, in the south. As the opening sequences tell us, Lodis canonically conquered most of Ovis 15 years ago, nominally to impose its state-backed religion of Lodisism upon the heretic Ovidian people. However, in doing so Lodis underestimated the Ovidians’ resentment of subjugation and thought-policing, and the island mounted a series of rebellions against Lodisian domination, encouraged therein by Rananculan troops from the north looking to take advantage of the situation. Inevitably, Lodis crushed these uprisings heavy-handedly.

Fast-forward to the present, and a band of Lodisian knights under the leadership of pompous soldier-priest Rictor Lasanti is ship-bound for Anser. The group’s ostensible objective is to investigate tidings that Rananculan troops are once more fanning the flames of Ovidian insurrection. Amongst the sailing party we find our adolescent, titular ‘knight of Lodis’, Alphonse Loeher, who looks up to Rictor as both mentor and friend. Little does Alphonse know that this time around, the notion of fifth-columnists supported by Rananculus is sheer fiction to obfuscate the Rictor mission’s true purpose: to investigate rumours that the long-lost, mythical Sacred Spear, a weapon of otherwordly power, has resurfaced.

In actuality, both Rananculus and the Duke of Felis, Rictor’s father and subject of Lodis afflicted by folie de grandeur, are after it for their own nefarious purposes. Alphonse is left entirely in the dark on task force’s true objective until he collapses into the ocean after gallantly foiling an assassination attempt on Rictor, soon assembling a motley supporting cast to begin reconciling conflicting information on the true goings-on in Ovis.

I really, really like this narrative setup as it provides all the necessary ammunition to insert the classic Shakespearean themes of divided loyalties, megalomania, betrayal and so on, which Knight of Lodis happily does. But KoL goes one step further and layers in more unusual leitmotifs to round out the narrative experience. Conquest is an obvious one: Rananculus and Lodis are locked into an uncomfortable balance of power that, ironically, neither is seeking to break unless – echoing Sun Tzu – they can win whole and overwhelmingly. (Enter the Spear.) Themes of conquest, however, are ubiquitous in gaming and I won’t dwell on them further here.

More boldly, KoL actively touches upon the historically fraught relationship between church and state. Gaming space is usually dominated by absolute monarchs in one veil or another, but unconventionally Lodis is an reformed theocracy, its erstwhile Pope – who wielded both religious and secular authority – now deposed in favour of worldly lords. This displeases the pious undercurrent of Lodis’ society, giving birth to a nebulous underground organisation seeking to restore Papal power. This movement is personified by the grey eminence that is sorceress Cybil, who as Hand of the Pope heads up the presumed ‘Faith Militant’ of the Ogre Universe.

Throughout the game Cybil clashes repeatedly with Rictor, who as designated heir of Felis and the Duke’s chosen vehicle for his megalomania has a vested interested in erasing the Papists. (Handily Rictor is also a High Priest in the Church of Lodis, where loyalists grant him nifty inside information into the papal cabal’s activities, including their own hunt for the Spear). As both factions increasingly butt heads, Lodis pivots on the brink of civil war with Ovis as its proxy territory. Alphonse finds himself uncomfortably in the middle, forced to eventually decide between his long-standing allegiance to Rictor or siding with newfound guru Cybil, who opens his eyes to the dark side of Lodis’ exploits. And then Rananculus gets involved…

But besides being an unabashedly political RPG, Knight of Lodis is also a gripping coming-of-age story. (Which continues in the equally excellent Let Us Cling Together for PS1, by the way). As a 15-year old youth, Alphonse struggles with the notion of responsibility for his actions; the idea that outcomes can be zero-sum and irreversible, friends turning enemies, never to be friends again. Yet in the face of this formative, ultimately life-and-death choice, KoL offers a tiny bright spot: dare to follow your heart if it tells you to question the justness of established order, and allies shall be found in unexpected places. Canonically, Alphonse sides with the sage Cybil, aligning him with the Church and soaking up her quasi-philosophical wisdom of the ages. But Rictor’s steady hand is there for you too, if you want it. Who will guide you?

I want to insert a brief aside here to draw some inevitable comparisons with that other great tactics game, FFTA. First, the absence of a sense of consequence that is so tightly woven into KoL’s fabric has always irked me about Final Fantasy Tactics Advance. Nowhere is this more obvious than in the plot. FFTA has the player join a ‘clan’, suggesting that we may get involved in all manner of sub rosa wheeling-and-dealing and explore the dark underbelly of Ivalice. And while, through our actions as a clan, we slowly come to understand – spoilers! – just how much Ivalice mirrors Mewt’s wishes and desires, it remains a skin-deep dream world. The vast majority of FFTA’s 200+ side-missions float freely, failing to truly flesh out the consequences of Mewt’s increasingly restrictive rule for Ivalice’s variety of magical inhabitants.

Because, for one thing, nobody ever perishes. The stakes aren’t life or death. FFTA’s characters are invincible outside of the select area of lawlessness (the so-called Jagds), meaning that if one falls in combat they’re simply ‘knocked out’, to be revived in perfect health after the engagement. And while FFTA’s rules of engagement suggest business, featuring a battlefield ‘judge’ and a ‘prison’ for offenders, this supposed penal system is hardly of Shawshank-calibre, its harshest penalty to suspend a character for the remainder of the battle. The stakes, then, are a lump on one’s head and a 1000GIL fine payable in full to the wardens of Sprohm prison. Operating in this space, clans sometimes feel as though they exist just to facilitate standalone contract-style missions such as herb-picking and destroying toony troll bombs that bear no relation to the central problematique of its world. Their narrative potential goes underutilised.

Knight of Lodis is the polar opposite and tries its hardest to both craft a unified sense of realism and be internally consistent in its presentation. Its characters have complex emotions and divided allegiances. Its locations are imposing castles, scorched villages, and deserted ruins. Its stunningly beautiful, yet subdued colour palette reinforces the bleakness of Alphonse’s situation. All work in tandem to shape an atmosphere appropriate for Alphonse’s plight, who, having broken away from his former comrades riding Machiavellian machinations, is essentially a disinherited knight braving exile, choosing to instead follow his personal moral compass to trudge through the lands of a client-state that doesn’t want him there to stop two states from starting a catastrophic war. (And breathe!) Everything KoL does breathes this reality, singing from the same hymn sheet throughout to great effect.

On a mechanical level, FFTA and KoL are siblings, but not twins. The differences between their tactics mechanics are seemingly minor, but their gameplay impact is disproportionate. (I am going to assume here that you have a basic understanding of how ‘tactics’ games work; if not, break out the popcorn and switch on an LP of Let Us Cling Together on YouTube – GetDaved’s is great.)

Take counterattacks, for instance. This concept is absent in FFTA, meaning that it’s entirely risk-free to throw body after body at a hard-hitting enemy. With foes are deprived of the ability to counterpunch (or perma-kill) an attacker, the player is discouraged from fully exploiting terrain advantages (such as height differentials) and putting serious thought into the positioning of soldiers. KoL’s straightforward but highly effective solution is to greet any melee attack not made from behind – i.e. a frontal swing or sideways slash – with a counterblow that, depending on both characters’ stats, may exceed the attacker’s damage output. Indiscriminate bludgeoning of a foe thus becomes a costly – and possibly fatal – endeavour, especially when combined with the AI’s routine level advantage.

Another mechanical difference is KoL’s system of party-wide movement. In FFTA, turns are taken on an individual basis. This means that with an overlevelled or exceptionally fast party (of say Ninja and Assassins), all six of your guys move before the enemies do, and on FFTA’s narrow tactical maps, this means closing in to strike (often fatally) before foes get a chance to act. Particularly in the late game, battles are often decided before they’ve begun. Not only are KoL’s arenas bigger, each side of eight units alternating – not six – makes it terribly unwise to rush in like a fool where angels fear to tread. Indeed, party-wide movement is a double-edged – ahum – sword: while it allows you to swarm and pick off individual enemy soldiers, the AI may equally focus down exposed troops. Should physically vulnerable Clerics or Sirens be caught out of position, permadeath ensures they may not live to tell the tale. Party positioning is key.

The last mechanistic aspect I want to touch on is the difference between KoL and FFTA’s elemental systems. Again, I very much admire the course Knight of Lodis has taken in this department. FFTA recycles the Final Fantasy series’ staple Fire, Thunder, and Blizzard magics, and grants use thereof exclusively to a single class, the Black Mage. In combat, they function in a rock-paper-scissors configuration of spell effectiveness against particular foes.

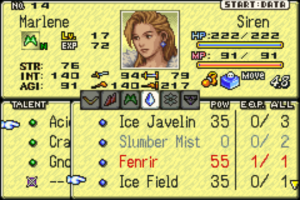

Knight of Lodis harnesses elemental balance very differently and with much greater depth. Its wide body of spells (and summons) – from Ice Javelin to Crag Crush to Fiend’s Grip – each belong to a particular element (Water, Fire, Wind, and Thunder, plus the more exotic Virtue and Bane). It then divides these into three groups, Water-Fire, Earth-Wind and Virtue-Bane, each moiety super-effective against the other half. So far, so standard. However, each soldier on your roster has an out-of-the-box elemental affinity that predisposes them to a certain strand of magic. While a troop can equip and use spells freely within the boundaries of their class restrictions (they come in rotatable scrolls), magic that matches the user’s elemental alignment will deal additional battlefield damage that is further multiplied if the enemy aligns with the immediately opposing element. For example, Crag Crush (Earth) will pack an extra punch when the casting Siren is also Earth, but will be utterly devastating if the target is Wind. Weaponry and armour is also elementally classified, so calculations factor these in. Needless to say this system massively expands upon standard rock-paper-scissors trinities and encourages diversified elemental coverage of soldiers, equipment and magic.

It doesn’t stop there, though. KoL builds out this system further by granting a maximum of one to four spell slot depending on a character’s class. For example, Knights may wield a single Healing spells, Ninja have a slot for a single-target or support magic, Witches can juggle three support spells simultaneously including the exclusive Fluid Magic, and MP-powerhouses Sirens and Summoners can pack a fully diverse roster of four magics. However, since even dedicated spellcasters are restricted to four spells, the player is forced into trade-offs. Do I opt for cross-elemental coverage to play off the Siren’s innately high INT-stat, or do I go all out on matching elements with a single-target, AoE, summoning and support spell of, say, Earth only? With the interchangeability of scrolls in lieu of perma-learned magic, infinite setups are possible depending on the impending battle. To invoke a Pokemon simile: if FFTA is content to grant each ‘Mon an ever-expanding movepool, Knight of Lodis encourages mixing and matching to uniquely strategise with just 4 swappable moves, making for a more meaningful experience.

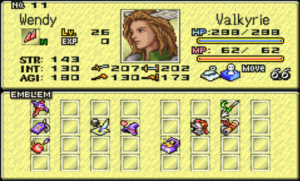

Alright, so much for the KoL-FFTA comparison. Before wrapping up this retrospective I’d like to highlight one more unique feature of Knight of Lodis: its emblem system. I absolutely adore it. Emblems are character-specific rewards for achieving combat feats, such as evading a would-be lethal attack (Miracle), killing 2 enemies simultaneously with single spell (Philosopher’s Stone) or, as female character, persuading a foe of the opposite gender to join your team (Vixen’s Whisper). Some are purely for show, others confer neat stat bonuses to agility, strength or intelligence, while a handful are the key to unlocking a more advanced classes for that character.

Vixen’s Whisper, for instance, is required to become a Witch; Knight’s Certificate, awarded for incurring a set number of counterattacks, is the gateway to the Knight class. Together with ‘hard’ stat requirements for strength, agility and intelligence, these form a soft barrier to class advancement. The fact that class progression hinges on battlefield accomplishments that tie in directly with the new class’ orientation (in lieu of a grind to accumulate a predetermined number of Ability Points) is a unique idea I haven’t seen replicated elsewhere. It crafts a mini-personality for an otherwise depersonalised character, or to put it differently, it forges a micro-story connecting the player to their pawns. In KoL’s fantasy-realist setting, this works really, really well.

Of course KoL is not without bugbears. Most noticeably, the battle pace is agonisingly slow. Action selection is sluggish, and characters stroll across the battlefield without the remotest sense of urgency, taking their sweet time to perform anything from using a consumable to delivering a spell. I don’t know why this should be so – I’m inclined to wag the finger at GBA’s processing power, though Advance Wars, a game in the same tradition, never had such issues. I’m certain that our former selves, equipped with lengthy pre-smartphone attention spans, minded this vice less, but today I invariably reach for the turbo-button.

The AI could also be a little more sensible. Early on it does an underwhelming job of focussing down exposed troops and tends to half-team suicide rush into your frontlines as you wait them out near the map’s edges, which can be construed as either poor programming or an act of generosity. The AI does wisen up a bit over time as it adopt tactics of strategic patience, expecting the player to bridge the distance between the warring parties and targeting your frailer soldiers with spells and arrows as you go.

In general, however, with a feel for balanced party composition – i.e. physical fighters of various stripes mixed with wizards and a stray cleric – most missions won’t push the player too hard. And while it is perfectly possible to lose a well-groomed regular due to unpreparedness or reckless play, the game is quite forgiving of lapses and losses. New characters can be hired at shops, and a fresh-faced lv1 recruit can be put through Training Mode to swiftly catch up with more senior brethren. There seldom will be mission re-do’s here, unlike in PS1’s Let Us Cling Together or fellow strategy game Advance Wars 2.

Then for all of KoL’s glory, there is a problem with story bookkeeping. As said before, the plot is artfully convoluted, and it would therefore be really nifty to have some means of recapping the story after each event – think diary entries in Dishonored 2, or a run-off-the-mill RPG journal. This is not so much a problem in the sense of finding one’s way to the next objective – Alphonse traverses a chart-like world map where destinations open up one by one to railroad the player from mission to mission – but more in the sense of tracking the who-is-who of Ovis and its the plenitude of factions and shifting alignments. It’s a true pity that retaining a full grasp of proceedings requires a serious brain training exercise, because that risks devaluing a core aspect of the overall experience, i.e. appreciating the superbly crafted and well-told story.

Nowadays, of course, such imperfections would be easily patched out in a post-release update. (Are you listening, Atlus? Fine-tuned Virtual Shop re-release, please!) If the player is prepared to engage with the story and tactical gameplay on the game’s terms, however, then all are forgivable offences.

There is more to say – Quest Mode, where the player can complete episodic battles in a pre-set turn limit to earn unique equipment; VS Mode, which allows battles against a friend, again for juicy rewards, and ‘I Want To Play This Again Mode’ to side with whoever you hadn’t sided with before. But I think you get it, and I admit it: this retro review is a love letter. Knight of Lodis employs the same addictive tactics-formula as its more famous counterparts, and endows it with both narrative and mechanical depth that peers FFTA and Onimusha Tactics are left pining for. I will go on record and say that Knight of Lodis is the best strategy RPG, if not outright the best RPG of any kind, on Gameboy Advance, and I think you should play it.

What’s that? Borrow my copy? Eh, over my perma-dead body!

- Harvest Moon 3 (2001) - March 5, 2020

- Pokémon Trading Card Game 2 (2001) - February 5, 2020

- Yu-Gi-Oh! Dark Duel Stories (2002) - January 5, 2020