The bucolic town of Vale, populated by ordinary-looking human sorcerers called Adepts, is rather unfortunately situated on the slopes of an active volcano. In the game’s opening scenes we are proffered the impression that it is about to erupt, and a pair of teenagers by the names of Isaac, a frail blonde kid, and his burly companion Garet scramble out of harm’s way and evacuate to a safe haven. From thereon, a grand adventure ensues in Camelot’s Golden Sun for GameBoy Advance.

—

During their escape, Garet and Isaac stumble upon a pair of miscreants that look like crossovers between DragonballZ’s Chao-Tzu and Vegeta jabbering away about a mysterious temple – the Sol Sanctum – hidden in the village. Isaac and Garet’s luck runs out when the semi-Saiyans take umbrage to being eavesdropped, and with a flew blows the boys are knocked unconscious. Meanwhile, calamity strikes as a boulder the size of a petite castle is ejected from the volcano, barrels down the mountainside and takes a house and few unfortunate folk with it, including Isaac’s dad and a kid trapped on a log in a river. (Lava is conspicuous in its absence.)

During their escape, Garet and Isaac stumble upon a pair of miscreants that look like crossovers between DragonballZ’s Chao-Tzu and Vegeta jabbering away about a mysterious temple – the Sol Sanctum – hidden in the village. Isaac and Garet’s luck runs out when the semi-Saiyans take umbrage to being eavesdropped, and with a flew blows the boys are knocked unconscious. Meanwhile, calamity strikes as a boulder the size of a petite castle is ejected from the volcano, barrels down the mountainside and takes a house and few unfortunate folk with it, including Isaac’s dad and a kid trapped on a log in a river. (Lava is conspicuous in its absence.)

Fast-forward three years from the eruption and the enigmatic semi-Saiyans are back in town, now lurking outside a wooden cabin on Vale’s outskirts. It’s property of a dishevelled-looking fellow by the name of Kraden, Vale’s resident scientist who sports impressive gray manes for a beard. As it turns out, Kraden is also a would-be alchemist, as he’s spent his life hunting for certain all-powerful Elemental Stones that are the gateway to the world’s magic. Yet for all his intellect, he somehow never thought to probe the depths of the obviously magical Sol Sanctum right nextdoor. That is, until the Saiyans – who are called Menardi and Saturos, by the way – planted the seeds of this idea in his mind.

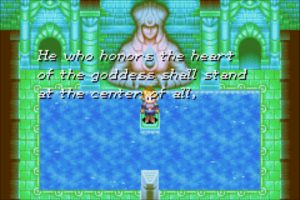

Recruiting Isaac and Garet to his cause, Kraden dragoons them into exploring the heart of the sanctum. As they stumble upon the mystical Elemental Stones, Kraden encourages the boys to lift them from their retaining pedestals. At this point Menardi and Saturos predictably turn up and handily relieve the boys of all but the Fire Stone, thanking them for a job well-done and kidnapping the alchemist and Garet’s sister to boot. Here we learn from a weirdass floating eyeball that the Elemental Stones are used to ignite Lighthouses, and should this occur – which is presumably the Saiyans plan – some tragedy equals parts unspeakable and unspecified will befall the world. And with that, Golden Sun’s opening sequences finally conclude and we can leave Vale to strike out into the wider world.

Recruiting Isaac and Garet to his cause, Kraden dragoons them into exploring the heart of the sanctum. As they stumble upon the mystical Elemental Stones, Kraden encourages the boys to lift them from their retaining pedestals. At this point Menardi and Saturos predictably turn up and handily relieve the boys of all but the Fire Stone, thanking them for a job well-done and kidnapping the alchemist and Garet’s sister to boot. Here we learn from a weirdass floating eyeball that the Elemental Stones are used to ignite Lighthouses, and should this occur – which is presumably the Saiyans plan – some tragedy equals parts unspeakable and unspecified will befall the world. And with that, Golden Sun’s opening sequences finally conclude and we can leave Vale to strike out into the wider world.

Let’s get this off my chest: Golden Sun (GS) is not a terribly innovative game. Its premise resembles every Japanese-made RPG since the dawn of time: as so often, an X-number of kids set out to save the world from two-dimensional evil. In its execution of JRPG-fantasy tropes, however, Golden Sun is truly exceptional. I put this down to the happy confluence of talent at Camelot – the brains behind the Shining Force and handheld Mario sports series – and a copious 18 months of development time: an exceptionally long cycle for a GBA game. Altogether it rubbed off to create Chrono Trigger-like production values in every single department, from art and environmental design to the combat system and character animations.

Golden Sun’s incredible attention to detail is most immediately obvious in the artstyle, which I’m totally smitten with. It’s best described as loosely pixelated with pointillist qualities that are undoubtedly part conscious artistic choice and part restriction imposed by the limited rendering power of the 8-bit GBA and the need to cram a lengthy, adorned JRPG into a paltry 4-32MB storage cartridge. Yet to game’s credit it never feels as though the graphics department laboured within constraints of an early-day handheld; even if the game were first released today on 3DS with its vastly superior aesthetic capabilities, Golden Sun’s visuals would concede no reason to consider it any less than graphically charming.

Because Golden Sun fully exploits the opportunities its fluid style affords it. A want of tight lines sees GS play with colour and shadow to produce vivid contrasts and stretch the GBA’s colour palette to the limit. It’s hard to put into words really; it’s like having the privilege to watch, say, the visual splendour of Life of Pi on Blu-ray while the rest of Hollywood was still releasing on VHS.

It helps that environments are varied and meticulously detailed, which is a far-cry from, say, the prefab towns and empty castle corridors of Final Fantasy V on SNES. Compact urban environments are jam-packed with NPCs that reside in richly decorated homes going about their daily business. Yes, RPG’s cliched ‘biome towns’ do make an appearance (one in the desert, tundra, velvet hills, coast etc) but to its credit Golden Sun deepens the distinction to more than mere colour scheme and an occasional sandstorm and snowstorm. Specifically I like that Camelot went the extra mile to extrapolate what would it mean to actually live at foot of a mountain or at the arctic circle or in middle of desert, meaning that you’ll see precarious rope-bridges, iced-over rivers and mid-town oases depending on the locale.

It helps that environments are varied and meticulously detailed, which is a far-cry from, say, the prefab towns and empty castle corridors of Final Fantasy V on SNES. Compact urban environments are jam-packed with NPCs that reside in richly decorated homes going about their daily business. Yes, RPG’s cliched ‘biome towns’ do make an appearance (one in the desert, tundra, velvet hills, coast etc) but to its credit Golden Sun deepens the distinction to more than mere colour scheme and an occasional sandstorm and snowstorm. Specifically I like that Camelot went the extra mile to extrapolate what would it mean to actually live at foot of a mountain or at the arctic circle or in middle of desert, meaning that you’ll see precarious rope-bridges, iced-over rivers and mid-town oases depending on the locale.

More so, many of these towns have distinctive architectural features. The Chinese-themed hamlet of Xian comes to mind, which is replete with a silkworm-infested mulberry orchard, a somehow Koi-free Lotus pond, turquoise curved roof structures, toro standing lanterns (which are actually Japanese, but whatever), Dao-symbolism in the peculiar appearance of giant ying-yang carpets and – for a bonus point – a historically accurate inn bearing the sign 宿 over its double sliding doors that somehow open inward.

I could go on and on about such detail. Water ripples across ponds and splashes placidly against the struts of a protruding pier. The low-hanging sun casts the shadow of a bridge’s handrail across the woodwork. As you traverse the snow-coated city of Imil, little footsteps are left in the snow. There is not an opportunity for adornment that has gone unseized.

This extends to the protagonists themselves. Much like in fellow handheld experience Knight of Lodis, characters are not inanimate sprites when stationary. Rather, their heads bob gently from side to side as they take in their surroundings and blink their watercolour eyes to refresh their vision. It is such fine touches that make Golden Sun come alive an extent I haven’t seen elsewhere on GBA, and is rare even on classic DS. Contemporary critics picked up on this, too, and in lofty praise proclaimed GS could match best of the computationally superior SNES titles.

That said, if you were concerned this review was drifting towards an uncritical paean, worry not. Paradoxically, Golden Sun’s level of polish conspires against it from time to time. On the one hand, I love how characters pace back and forth in alarm when stumbling upon some particularly brain-bending development, and how goofy little animations in the style of Final Fantasy on SNES appear over characters head to reinforce sensations of glee, surprise, frustration and so on. But they are overused and these sequences go for so long. Each time something plot-poignant happens we are treated to the spiritual successor of the game’s opening hour as the characters work – and it pains me to say it – through prosaic and often uninspired dialogue.1And if I wanted to be harsh, I could make the argument that the whole reason these visual exclamation points are even amusing or necessary is because GS’ writing is uniformly devoid of emotional payload – much like in Final Fantasy V where these are also a dime a dozen. I can’t help but wonder if the lengthy dev-time is actually a bane, not a blessing, in this regard, since tighter time constraints would likely have prevented over-adornment, even if it wouldn’t have saved the script. (Yes, I know, there is no pleasing me.)

It’s not an entirely ludicrous notion though, since the ‘too much polish’ problem rears its head in other segments from time to time. Take the game’s intro sequences. Between scenes set in the past – which should reasonably have been a flashback! – and the prelude to the inevitable au-revoir, an hour-plus goes by in which precious little action takes place. Surely Camelot could have told this vignette much more succinctly had the entire boulder-affair I mentioned earlier been a cutscene and the gameplay picked up with the Saiyans outside Kraden’s house.2The irony is that timewarp-cutscenes like the one I proposed above are used to great effect elsewhere in the game. Especially since hardly any of it is plot-pertinent. Narratively-speaking, the hour-long boulder calamity is but an extremely elaborate pretext to make the aforementioned kid in the river – Felix – disappear so that, three years later, he can turn up alongside the baddies and sow confusion as to their true intentions. Nothing else of import happens during this time – including, sadly, the tragic death of your father, a narrative tool with oodles of emotional potential that goes entirely, and I mean entirely, unused in the character of silent protagonist Isaac.

It’s not an entirely ludicrous notion though, since the ‘too much polish’ problem rears its head in other segments from time to time. Take the game’s intro sequences. Between scenes set in the past – which should reasonably have been a flashback! – and the prelude to the inevitable au-revoir, an hour-plus goes by in which precious little action takes place. Surely Camelot could have told this vignette much more succinctly had the entire boulder-affair I mentioned earlier been a cutscene and the gameplay picked up with the Saiyans outside Kraden’s house.2The irony is that timewarp-cutscenes like the one I proposed above are used to great effect elsewhere in the game. Especially since hardly any of it is plot-pertinent. Narratively-speaking, the hour-long boulder calamity is but an extremely elaborate pretext to make the aforementioned kid in the river – Felix – disappear so that, three years later, he can turn up alongside the baddies and sow confusion as to their true intentions. Nothing else of import happens during this time – including, sadly, the tragic death of your father, a narrative tool with oodles of emotional potential that goes entirely, and I mean entirely, unused in the character of silent protagonist Isaac.

Another example is when setting sail across a small island sea, which requires a series of rituals and interactions of Byzantine complexity relative to the simple objective of lifting anchor. Moreover, the voyage itself is interrupted by multiple scripted attacks from sea monsters, necessitating repeated do-overs of mundane damage-control tasks while sitting through same cutscenes each time. It’s altogether a case of what the Mandarin-speaking people of Xian might call 畫蛇添足, or “drawing legs on a snake” to symbolise excessive embellishment. In fairness GS only seldom succumbs to over-adornment and calling too much attention to this flaw is probably like obsessing over tiny speck on what is otherwise the Centenary Diamond. But hey, all is forgiven, for once the game mechanics come into their own and the story picks up somewhat, Golden Sun places a tight grip on your free time that never lets go.

The game’s compelling nature extends to how Golden Sun’s magic – called Psynergy – is deployed as a unifying element throughout Golden Sun’s universe. “Magic” in the broadest sense is perhaps the most stale and predictable component of JPRGs, good for blasting mobs to smithereens in random encounters and perhaps lending a dash of whimsy to the gameworld but not much else. In Golden Sun, however, Psynergy is baked into the very fabric of its overworld as it is used in numerous puzzles from start to finish. And since it is so clearly ubiquitous, its utility in combat feels like a natural extension rather than a mindless necessity.

Outside of combat, Psynergy is the foundation for environmental puzzles that have a Zelda-esque feel to them, but rather than the latest gizmo you will use an expanding pool of spells to Move, Lift, Force, Catch, Freeze, Grow and Reveal objects. In the early game especially, most of the puzzles that gate beckoning treasure chests can be quickly pigeonholed as applying spell X to object Y to create outcome Z. While such simplicity would be a clear indictment for a Zelda game, in Golden Sun I think it is actually a boon as it helps maintain a satisfying sense of progress at all times. GS understands that the death knell of any and all RPGs is to design a puzzle that bars progress completely, and in my opinion frequent and accessible challenges are in most situations vastly preferable over the occasional but mind-bending in terms of enjoyment.

Outside of combat, Psynergy is the foundation for environmental puzzles that have a Zelda-esque feel to them, but rather than the latest gizmo you will use an expanding pool of spells to Move, Lift, Force, Catch, Freeze, Grow and Reveal objects. In the early game especially, most of the puzzles that gate beckoning treasure chests can be quickly pigeonholed as applying spell X to object Y to create outcome Z. While such simplicity would be a clear indictment for a Zelda game, in Golden Sun I think it is actually a boon as it helps maintain a satisfying sense of progress at all times. GS understands that the death knell of any and all RPGs is to design a puzzle that bars progress completely, and in my opinion frequent and accessible challenges are in most situations vastly preferable over the occasional but mind-bending in terms of enjoyment.

That is not to say that on occasion, particularly in the Lighthouses that most closely resemble Zelda’s dungeons, the game won’t throw a brainteaser your way. Oddly, these don’t rely on physical manipulation by Psynergy much. In general you’ll benefit from paying close attention to things like (impressive) level layout and thinly veiled text clues to tease out what, where, and how to use Psynergy in a new situation. If you don’t, well… As a boy in the early 2000s, Mercury Lighthouse had me stumped as I, first, failed to realise I could pass through a waterfall, and then couldn’t think to cast healing spell Ply to appease a deity in return for water walking powers – this despite the game’s repeatedly dropping poetic hints suggesting the benefits of doing so.

Oddly, the greater risk of not knowing how to advance is by losing one’s bearings in the story. Inexplicably there is no quest log to help you track objectives so you must instead fully rely on memory of scripted events and fragmented hearsay from NPCs to find out where to go next, and how to get there. This is fine when playing the game for several days straight but pity your soul should take a week’s break and subsequently run around like headless chicken trying to trigger that next event prompt to get a renewed sense of what the hell was going on. Such want of recap is all too common in classic RPGs – including the aforementioned FF5 and Knight of Lodis – but I’ve rarely played one that would not benefit from a quest log and GS is no exception to this rule. Anyway, I’m getting side-tracked – Psynergy. As I said earlier, I had been bored with “magic” in JPRG’s ever since Final Fantasy VI came out in 1994 and the moment I understood how Golden Sun was innovating the JRPG combat system it immediately rose to the peak of my personal Mount Brilliance. In GS’ random encounter driven, turn-based combat, magic has all its familiar uses, but there’s a twist. Each of the four characters has a fixed elemental affiliation – Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Mercury (code for earth, fire, wind, and water) – but crucially none of the spells they unlock as they level up are hard-coded like Thundara, Blizzara etc might be. Rather, these spells – and the classes of your characters at large – vary depending on the elements of the mystical creatures called Djinni you assign to them, making for some wicked interactions and highly powerful magicks.

Oddly, the greater risk of not knowing how to advance is by losing one’s bearings in the story. Inexplicably there is no quest log to help you track objectives so you must instead fully rely on memory of scripted events and fragmented hearsay from NPCs to find out where to go next, and how to get there. This is fine when playing the game for several days straight but pity your soul should take a week’s break and subsequently run around like headless chicken trying to trigger that next event prompt to get a renewed sense of what the hell was going on. Such want of recap is all too common in classic RPGs – including the aforementioned FF5 and Knight of Lodis – but I’ve rarely played one that would not benefit from a quest log and GS is no exception to this rule. Anyway, I’m getting side-tracked – Psynergy. As I said earlier, I had been bored with “magic” in JPRG’s ever since Final Fantasy VI came out in 1994 and the moment I understood how Golden Sun was innovating the JRPG combat system it immediately rose to the peak of my personal Mount Brilliance. In GS’ random encounter driven, turn-based combat, magic has all its familiar uses, but there’s a twist. Each of the four characters has a fixed elemental affiliation – Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Mercury (code for earth, fire, wind, and water) – but crucially none of the spells they unlock as they level up are hard-coded like Thundara, Blizzara etc might be. Rather, these spells – and the classes of your characters at large – vary depending on the elements of the mystical creatures called Djinni you assign to them, making for some wicked interactions and highly powerful magicks.

Let me explain. Djinni are huggable, gerbil-like fellows that became scattered throughout the world the moment an unwitting Isaac disturbed the Elemental Stones. You round them up over the course of the adventure, mostly by solving environmental puzzles. (In fact, some of the game’s coolest moments flow from the gradual acquisition of new environmental Psynergies that will trigger audible ‘oooh!’ as mental cogs fall into place, followed by a bit of frantic backtracking to snatch that Djinn which had sat tantalisingly yet puzzlingly out of reach behind, say, ice pools that can now be frozen into pillars and leapt across.) Once under your wing, a Djinn can be assigned to a character for, in the first place, some serious stat buffs. Each fighter can hold up to 7 Djinni, which will eventually amount to a good portion of their health, attack, agility and so on.

Each Djinn also has a unique special ability. These range from inflicting a status condition such as Sleep or a Defence debuff on an enemy to highly useful party-wide stat and resistance buffs and assorted heals. Any Djinn can be assigned to any character at any time outside of battle. ‘Setting’ them, in the game’s parlance, to a character this way makes their ability available during a battle for that warrior only.

Each Djinn also has a unique special ability. These range from inflicting a status condition such as Sleep or a Defence debuff on an enemy to highly useful party-wide stat and resistance buffs and assorted heals. Any Djinn can be assigned to any character at any time outside of battle. ‘Setting’ them, in the game’s parlance, to a character this way makes their ability available during a battle for that warrior only.

That’s not all, though. After the Djinn’s ability has been activated, it’s exhausted and flips to standby mode (doing effectively nothing until recalled). From there, however, it can be summoned back into battle to unleash a powerful elemental attack upon a foe. It’s even possible to simultaneously recall multiple Djinn of matching elements, which leads them to bundle their forces and invoke, say, the godlike power of Thor to obliterate an enemy. And if passive stat boosts aren’t your style, Djinni can be put standby from the get-go, making any time hammer time.

You’ll gather that it’s a reasonably complex system with considerable depth, especially for a handheld game. At all times there are four Djinni dimensions to consider: an individual Djinn’s stat boost, which may be broad-based or focus on one aspect; a Djinn’s specific unique ability, which can be offensive or defensive in nature; a Djinn’s activation status, ready or on standby; and lastly a Djinn’s elemental affinity in relation to the hero’s and to other Djinni’s to create the desired spell combinations. Choices are zero-sum; what to go for will depend on the state of your party and the monster you’re staring down. This makes it so that assigning a specific Djinni is always a trade-off demanding careful consideration, and different sets of benefits can be switched between as circumstances demand.

I hope you’re still with me, because I haven’t yet fulfilled my promise of explaining how Djinn and Psynergy interact. In a nutshell: a Djinn’s elemental affinity cross-reacts with both their human master and the Djinni equipped to that human to create new spells that are elemental hybrids. For example, pairing Garet (Fire) with Water Djinn Venus results in a new combination spell. This matters because mobs, including bosses, are also elemental, meaning it can be very helpful to ele-spec characters for boss fights in particular to exploit their weaknesses (and patch up your own) and skirt around resistances (while bolstering yours).

I hope you’re still with me, because I haven’t yet fulfilled my promise of explaining how Djinn and Psynergy interact. In a nutshell: a Djinn’s elemental affinity cross-reacts with both their human master and the Djinni equipped to that human to create new spells that are elemental hybrids. For example, pairing Garet (Fire) with Water Djinn Venus results in a new combination spell. This matters because mobs, including bosses, are also elemental, meaning it can be very helpful to ele-spec characters for boss fights in particular to exploit their weaknesses (and patch up your own) and skirt around resistances (while bolstering yours).

In sum, by bolting Djinni on top of regular “magic” that is part and parcel of fantasy RPGs, and then creating space in the middle for cross-reaction between the two, Golden Sun has devised a highly dynamic combat system for players to tinker with that confers real, meaningful choice on how to tackle specific battles. The ultimate testimony to the success this formula is that with good strategy, one can afford to liberally apply monster-repellent Sacred Feathers to avoid grind and still do fine in boss fights on tactical merits. Yes, I think Camelot found the Holy Grail: it made an entertaining JRPG free from the mandatory timesink that is grinding for level-ups. I wish I could say that much about other classics of the genre.

The final regret I have is that Golden Sun ends all too abruptly. Its story continues in Golden Sun: The Lost Age (2002), which is by all counts a direct continuation and arguably the second half of a game intended to fit a single cartridge. But, so the rumour goes, Camelot was stymied by the GBA cart’s limited storage space. That’s fine, though. Golden Sun is an engrossing standalone experience, and rather than finding its want of conclusion unsatisfying, it fills me with delight to know that more of the same exists out there.

- Harvest Moon 3 (2001) - March 5, 2020

- Pokémon Trading Card Game 2 (2001) - February 5, 2020

- Yu-Gi-Oh! Dark Duel Stories (2002) - January 5, 2020